Historians collaborating with an artificial intelligence assistant have initiated the tracking of astronomical thought dissemination across Europe in the early 1500s. This analysis challenges the notion of scientific revolutions being driven by solitary geniuses. Instead, it reveals that knowledge about star positions was widespread and applied across various fields, according to researchers in a study published October 23 in Science Advances.

"We are witnessing the initial formation of a proto-international scientific community," states computational historian Matteo Valleriani from the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin. Valleriani and his team utilized AI to analyze a digitized collection of 359 astronomy textbooks published between 1472, just under two decades after the Gutenberg Bible's first printing, and 1650. These textbooks were foundational for teaching geocentric astronomy, which posits Earth as the central point of the cosmos, expanding outward through concentric spheres. Understanding star positions was crucial for disciplines ranging from medicine to classical poetry, making introductory astronomy classes mandatory for all students. Students were taught to use the sun's position within zodiac constellations to determine the date of ancient events, a practice essential before standardized calendars became prevalent.

Examining these historical texts provides insight into the general knowledge of the universe held by educated individuals and how this understanding evolved over time. The dataset encompassed 76,000 pages of text, images, and numerical tables, often with varied fonts, formats, and layouts. While a historian might analyze a few books in a lifetime, Valleriani and his team aimed to study all of them. "What we sought to understand was what students were learning in astronomy across these 180 years and throughout Europe," Valleriani explains. "This task was humanly impossible."

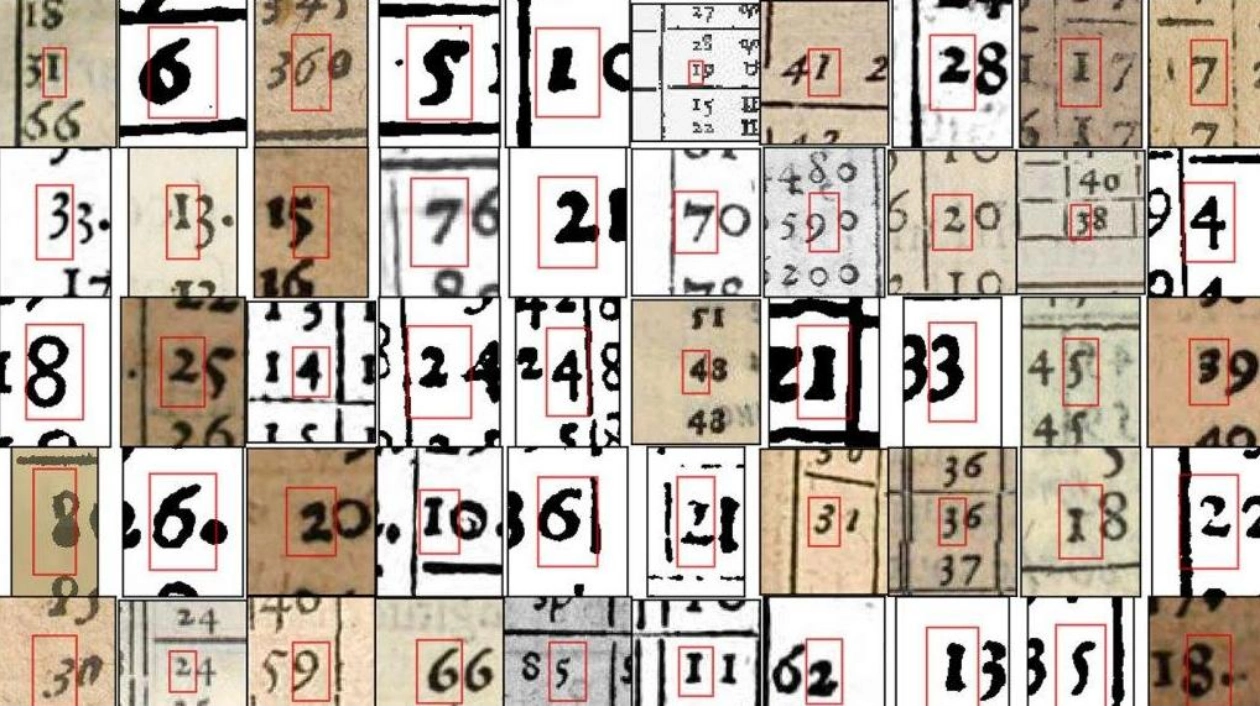

The team employed machine learning to identify 10,000 distinct numerical tables within the textbooks. They then trained an AI model to recognize individual numbers within these tables. "This was exceptionally challenging due to the inconsistent formatting of the tables," notes physicist and machine learning expert Klaus-Robert Müller from the Technical University of Berlin. "Everything is quite disorganized." After the AI extracted all numbers, it compared the tables, highlighting similarities and differences. Some textbooks were essentially reprints with identical tables, while others introduced novel ideas or methods for utilizing astronomical data.

Although the AI couldn't interpret the meaning of these similarities and differences, it provided a starting point for identifying trends or moments of change. "It's a shift from using AI as a tool to assist with preconceived tasks to treating AI as a team member, suggesting new solutions that I couldn't envision," Valleriani remarks.

A prevalent narrative about this era's astronomy highlights individual scientific heroes like Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler, who revolutionized the world by demonstrating that Earth is not the center of the universe. However, historians are increasingly moving away from the idea that science advances through such solitary geniuses. These discoveries were embedded in social, political, and cultural contexts and required dissemination into broader culture.

"When discussing the scientific revolution and the triumph of the Copernican worldview, we know the prominent names," says computational scientist Jürgen Renn from the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Jena, Germany, who was not part of the new study. "But in Europe, this was a widespread movement. There were numerous contributors." One significant finding from the team is that textbooks printed in Wittenberg, Germany, in the 1530s were extensively imitated across Europe. Books sold in larger markets like Paris and Venice fostered a unified approach to astronomy.

Valleriani finds this ironic, given Wittenberg's renown for being the birthplace of Martin Luther's Protestant Reformation, which led to a schism in Christianity. "It seems paradoxical," Valleriani says. "While Wittenberg and the Protestant Reformation were dividing Europe... and setting the stage for wars, at the same time, Wittenberg was developing an educational scientific approach that was truly adopted everywhere."

The team acknowledges limitations in this research. Historical data is always incomplete, and historians must select subsets of data to focus on. AI cannot account for such selection biases; human historians must remain integral to the process. This work demonstrates how historians can effectively use artificial intelligence methods in the future, emphasizing that AI is a powerful tool for understanding history as a broad flow of human actions and thought, rather than a series of isolated events.

Source link: https://www.sciencenews.org