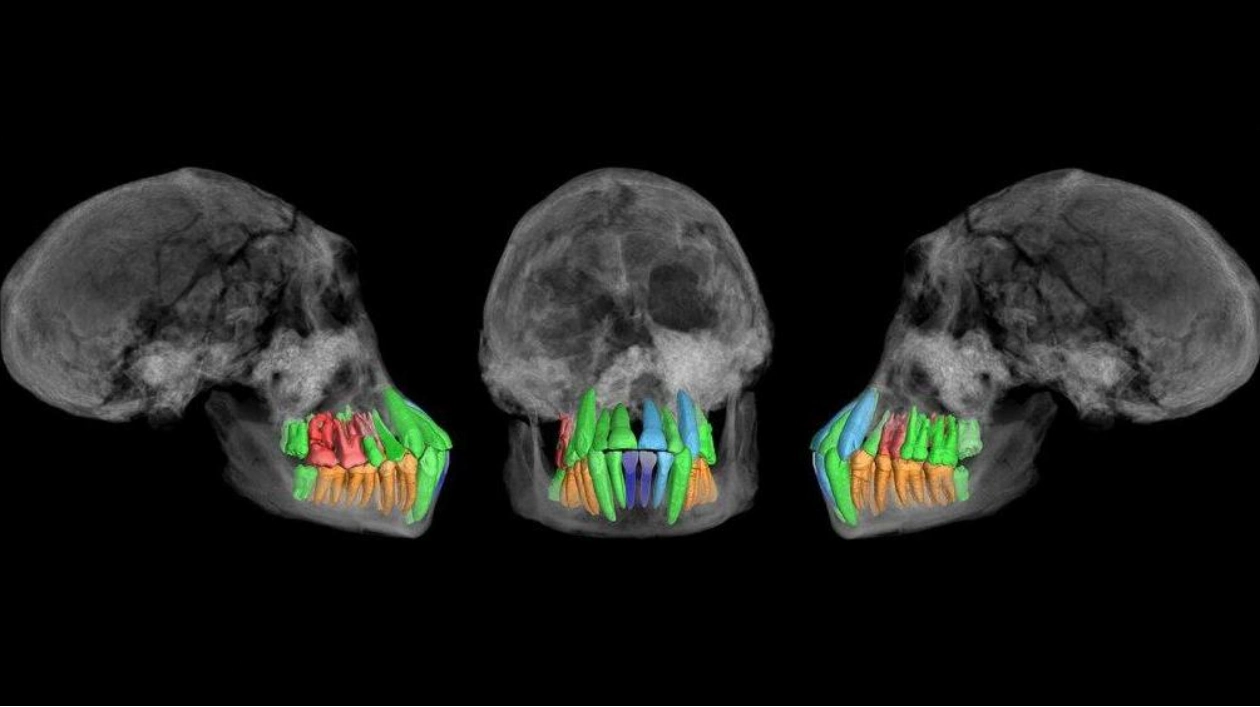

An extended childhood, a hallmark of human development, may have had an ancient and unusual beginning. A new study suggests that one of the earliest known members of the Homo genus experienced delayed, humanlike tooth development during childhood, followed by a more chimplike dental growth spurt. The fossil teeth of a roughly 11-year-old individual indicate slowed development of premolar and molar teeth up to about age 5, followed by accelerated development of those same teeth. This slower start represents an initial evolutionary attempt to extend growth during childhood, according to University of Zurich paleoanthropologist Christoph Zollikofer and colleagues. Their findings, based on X-ray imaging technology that examined microscopic growth lines inside the fossil teeth, were published on November 13 in Nature.

The youngster’s skull, along with four others unearthed at the Dmanisi site in Georgia, dates back to between 1.77 million and 1.85 million years ago. While some researchers classify these fossils as Homo erectus, Zollikofer’s group considers the Dmanisi specimens as an undetermined Homo species. Homo sapiens originated much later, around 300,000 years ago. Although a common belief is that a long childhood, slow dental development, and an extended lifespan evolved alongside brain expansion in H. sapiens, “that might not have been the case in early Homo,” Zollikofer notes. Homo individuals at Dmanisi had brains only slightly larger than those of modern chimps.

Zollikofer’s team offers the first “fairly complete” reconstruction of an ancient hominid’s dental development, says paleoanthropologist Kevin Kuykendall of the University of Sheffield in England, who did not participate in the new study. Previous studies of ancient hominid dental development have focused on fossil individuals no older than about age 4, Kuykendall adds. X-ray imaging allowed the researchers to estimate the extent of tooth growth at different ages during the life of the Homo youth, who died just before reaching dental maturity between 12 and 13.5 years of age. In contrast, dental maturity in people today occurs between age 18 and 22, while chimps reach dental maturity between 11 and 13 years of age.

If ancient Dmanisi individuals were our direct ancestors, then shared childcare, including grandmothers and unrelated helpers, may have driven the initial evolution of a longer childhood, Zollikofer speculates. Later, childhood growth slowed further as H. sapiens brains grew larger. If early Homo at Dmanisi belonged to a dead-end lineage, “then Dmanisi looks like a first evolutionary experiment with extended childhood,” Zollikofer says. These scenarios are possible, Kuykendall agrees. However, he argues that finding a slow start to tooth growth that did not significantly delay dental maturity could instead indicate one of many ways in which tooth development evolved among ancient hominids, including early Homo species that ventured into diverse habitats.

For instance, variations in available foods or age at weaning, rather than shared childcare, could have shaped dental development in early Homo groups, Kuykendall suggests. Paleoanthropologist Tanya Smith of Griffith University in Southport, Australia, says the new study fails to demonstrate that the Dmanisi youth had an extended childhood. She points to the study’s estimate that the Dmanisi first molar erupted at around age 3.5, closer to that of chimps than humans. Prior studies indicate that the timing of first molar eruption strongly predicts many aspects of dental and physical development, placing Dmanisi on a chimplike trajectory, Smith notes. The chimplike dental features of the Dmanisi youth are consistent with that individual’s small brain size, an even stronger indication of rapid overall development, Smith concludes.

Source link: https://www.sciencenews.org