In a different scenario, Christian Wade could have been donning the Bills jersey to face the Ravens over the weekend, instead of securing a hat-trick for Gloucester in their victory against Bristol on Friday. At 33, Wade has returned to the Premiership after a six-year hiatus, four of which were spent in the NFL, and two more playing rugby for Racing 92 in France. He has already grabbed headlines by expressing his ambition to surpass Chris Ashton’s record and become the league’s top try scorer (he requires 17 more tries to achieve this). Beneath his confident exterior, Wade has evolved into an intriguing athlete to converse with; older, wiser, and more reflective following his time away. He has experienced more than many in his profession.

Wade never actually stepped onto the field for the Bills in a regular-season game. He famously scored a 65-yard touchdown on his very first carry in a preseason match against the Colts, but that was the highlight of his NFL journey. For the next three years, he was in and out of the Bills’ practice squad, which is more commendable than it sounds. With over 73,000 college footballers in the US, and approximately 16,000 eligible for the 250 slots in the NFL draft, Wade was just another prospect, competing against individuals who were far more knowledgeable about the sport. Most of what he knew, he learned from “playing Madden”.

Wade’s background in American football extends beyond the NFL video game. He was first approached in 2015 by Jason Bell, Osi Umenyiora, and a couple of other NFL players. Fascinated by their belief in him, he spent his off-days during that rugby season secretly training at Tottenham, “learning how to catch the ball correctly, how to hold the ball correctly” and other fundamentals. The Jacksonville Jaguars offered him a contract based on his video footage, but he declined because he had just made the British & Irish Lions tour in 2013 and wanted to try for England at the 2015 Rugby World Cup. This decision mirrors Louis Rees-Zammit’s recent move.

Like Wade, Rees-Zammit entered the NFL’s international player pathway, designed to assist elite athletes from other sports in transitioning to American football. It’s a challenging path. A few have come close to breaking through, but only one has truly succeeded: the Australian rugby league player Jordan Mailata, now a standout offensive tackle for the Eagles. Wade mentions that he and Rees-Zammit are due for a catch-up, having exchanged text messages, but Rees-Zammit hasn’t found the time for a phone call yet. Wade understands this, as the hardest part of the transition was how busy he became. He had to catch up with his competitors, which wasn’t physical—Wade was strong and fast enough to hold his own—but mental, particularly mastering the playbook. NFL preseason days ran from 8am to 8pm, with two hours of training followed by eight hours of meetings and video analysis.

In the evenings, Wade would return home and have his wife “pretend to be the quarterback so I could practice all this stuff in the living room”. All those hours of work were crucial for those split seconds. “It’s one thing to run fast, but the amount of information you have to process before the snap is what will slow you down, because you’ll be thinking rather than moving. So that’s the challenge, and I think I saw a bit of that in Louis’s preseason games.” He recognized himself in Rees-Zammit and other UK players. “You’re fast, but you’re slowing down because you’re doing a lot of thinking.” Meanwhile, everyone else is playing on instincts honed by years of school and college football, the same way Wade does in rugby. “It probably took me two or three years to really get to that stage where I felt really comfortable,” Wade says. And that was when the injury happened. He injured his shoulder and was out for the season. The Bills cut him, even though he had two years left on his contract, leading him to return to rugby.

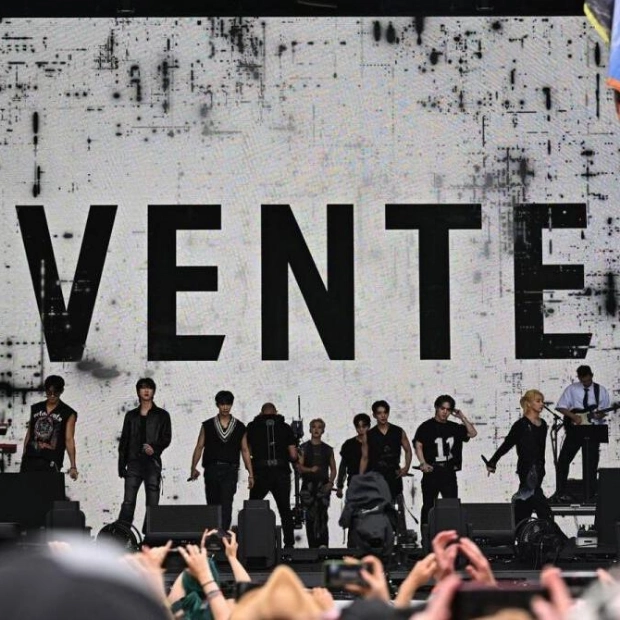

The Bills’ decisiveness highlighted another significant difference between the sports. Wade says the NFL can be more ruthless. It places a greater emphasis on individual responsibility. “The biggest difference was that the players are a lot more driven. They don’t need to be spoon-fed.” In the UK, especially in rugby, players can become too comfortable. “They can think: ‘I’m good at what I do, I’ve got three years on my contract, and I know I’m going to get paid even if they want to get rid of me.’” In the NFL, he says, no one will tell you to take extra care with your recovery or nutrition. You either do it, or you get cut. If the responsibilities were greater, so were the rewards. The NFL is one of the richest and best-run sports leagues in the world, and Wade has returned to a sport in a state of flux. He was speaking ahead of the NFL’s upcoming London Series of three fixtures at Tottenham and Wembley, part of a 17-year investment in overseas markets, which is paying off. Data from the ticket sales platform Viagogo shows that this year, for the first time, a majority of the paying fans for the series are from the UK rather than the US. The UK is now the NFL’s second-biggest market. There is always talk about the possibility of a London franchise.

Wade will keep one eye on it, watching with interest. But for now, his focus is on the try-line. “Rugby’s my sport,” he says, content to be back.