In 1926, Britain was a nation grappling with the aftermath of the First World War, revolution in the air, and widespread poverty. The General Strike of May, though short-lived, left deep scars of bitterness and recrimination. Millions of workers were sacked or locked out, and industries like coal mining ground to a halt. Amidst this turmoil, Australia’s cricket team arrived to defend the Ashes, a trophy they had decisively won in all three series since the war. Cricket, like everything else in England, was still recovering from the conflict, but the nation’s desperate need for success meant that interest in the Ashes transcended class and status.

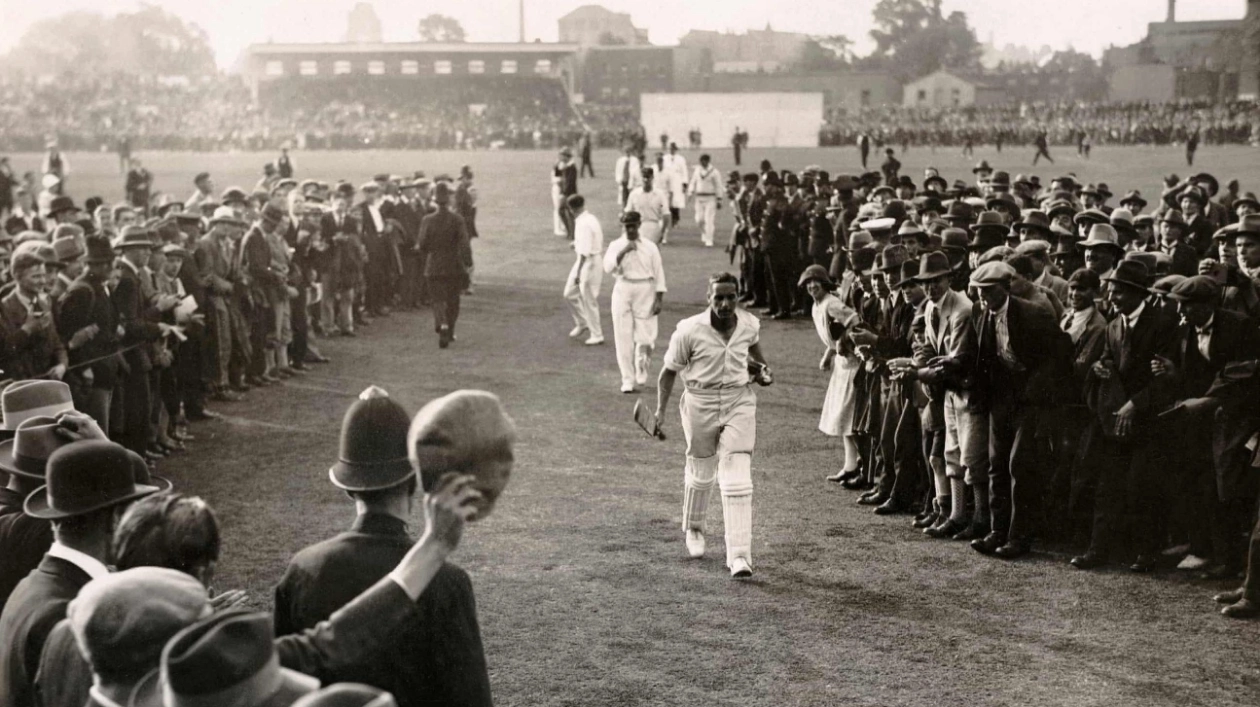

In his book, 'A Striking Summer,' Stephen Brenkley captures the drama of the series, delving into the personalities of the players and illustrating how, in such troubled times, cricket briefly united the nation. The extract highlights the extraordinary excitement that greeted the Australians’ arrival in England, despite the grave challenges facing the country. The train carrying the Australian cricketers arrived at Victoria Station on 18 April at 10pm, greeted by an estimated crowd of 30,000 to 50,000 people. The scene was chaotic, with police struggling to control the masses, and the tourists besieged by autograph hunters.

The Australians, having traveled from Dover via Naples and continental Europe, were overwhelmed by the reception. “I don’t think that ever in the annals of cricket either in Australia or here a team has been given such a welcome as we were given today,” remarked Sydney Smith, the team’s seasoned manager. The atmosphere was electric, with small boys, sailors, and Englishmen all joining in the festivities. The gathering marked the culmination of months of propaganda, with supporters and players trading jocular insults and predictions, a tradition that had become a staple of Ashes build-up.

The arrival of the Australians coincided with a critical moment in British history. The country was on the brink of a crisis, with the government’s nine-month subsidy to the coal industry set to expire on 30 April. The miners, supported by the Trades Union Congress, were on a collision course with the colliery owners, who demanded longer hours and reduced wages. The return to the Gold Standard, championed by Chancellor Winston Churchill, had overvalued sterling, leading to wage reductions and widespread hardship among workers. Yet, amidst this turmoil, the impending Ashes series became a welcome distraction, capturing the nation’s imagination.

Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, a cricket enthusiast, refused to let the affairs of state interfere with his passion for the game. Despite the looming industrial crisis, Baldwin found time to attend cricket matches and even hosted a luncheon for the Australian team at London’s Criterion Restaurant. The event, attended by cricket fan JM Barrie, featured whimsical speeches and toasts, with Baldwin joking about cricket and rabbits being exported to Australia. The PM’s devotion to the game was evident, as he compared the scrutiny faced by the England team’s chairman of selectors, Pelham Warner, with the daily challenges of his own office.

The anticipation for the 1926 Ashes series had begun as soon as Arthur Gilligan’s team left Australia in March 1925. With no Test matches scheduled in England that summer, the Ashes dominated sporting conversation, alongside the legendary Jack Hobbs, who had just surpassed WG Grace’s record of 125 first-class centuries. The euphoria surrounding Hobbs’ achievements showed that, despite football’s growing popularity, cricket remained the nation’s true sport. The northern outposts, where the effects of the strikes were most keenly felt, were also the heart of cricket and football success.

As the series approached, the focus shifted to the selection of the England team and its captain. Australia had already appointed its selectors and announced its touring party, but England’s old-fashioned policy of having an amateur captain sparked debate. The Melbourne Age derided the notion that a professional like Hobbs could never captain England, highlighting the conservatism that still dominated British cricket. Despite the challenges facing the country, the 1926 Ashes series became a beacon of hope, a brief moment of unity in a time of division.

Source link: https://www.theguardian.com