A vast Maya landscape has been concealed beneath a forested area in southern Mexico. The newly discovered city, named Valeriana, covers an expanse roughly equivalent to the size of Beijing and exhibits all the characteristics of a Classic Maya political capital, according to researchers in the October issue of Antiquity. Its plazas, interconnected by a grand passageway, towering temple pyramids, and a water reservoir would have likely impressed the Mayans over 1,500 years ago.

Archaeologists have long been aware of the presence of ancient urban settings in the Maya Lowlands, the southernmost region of Mexico (SN: 10/25/21). While examining random data online, archaeologist Luke Auld-Thomas of Tulane University in New Orleans stumbled upon a dataset being utilized by Nature Conservancy Mexico (TNC Mexico) to study carbon intake and emissions in the area. Intrigued by the high archaeological potential of the location, Auld-Thomas had a hunch that significant structures might be hidden there.

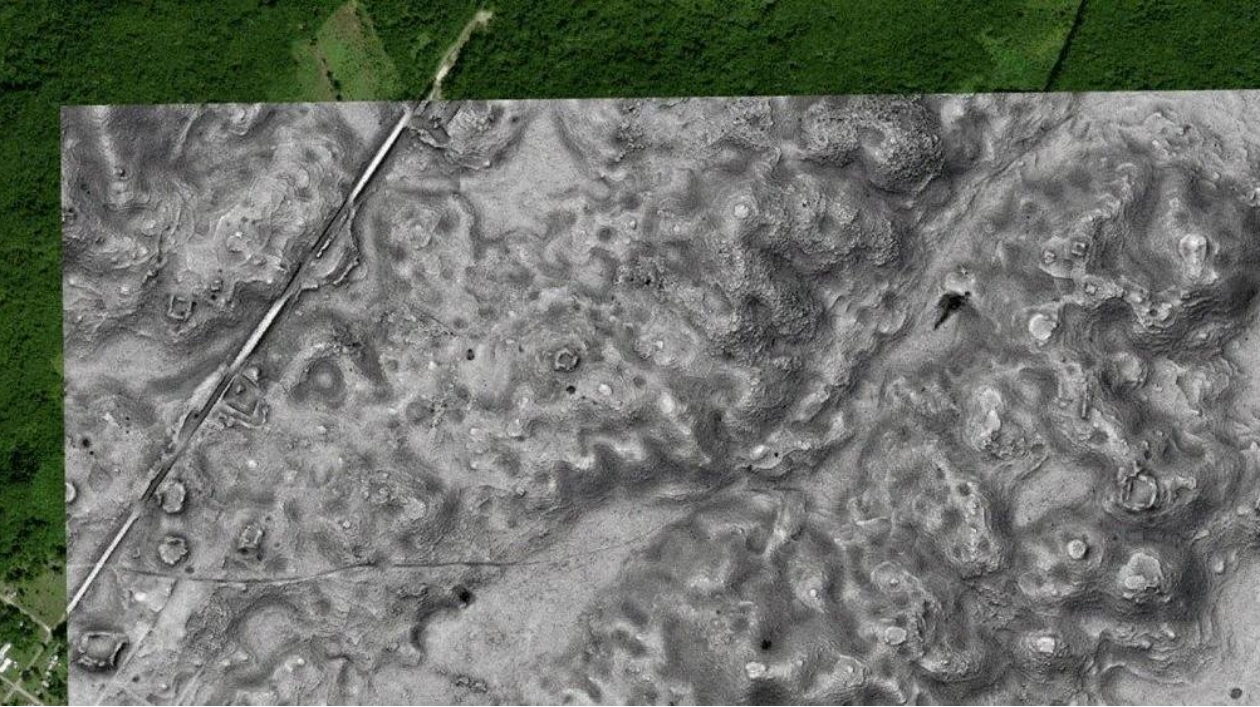

Further investigation confirmed his intuition. Auld-Thomas's discovery was likened to hitting the bullseye while blindfolded by Tulane anthropologist Marcello Canuto, who noted that such a large site was unearthed using a relatively small dataset. TNC Mexico's environmental analysis employed lidar technology to estimate tree heights and canopy volumes in the southern tip of Mexico. Lidar, which uses laser beams from aircraft to map landscape undulations, has previously uncovered numerous archaeological sites, including high-altitude Silk Road cities, a massive ancient urban complex in Ecuador, and long-forgotten urban sprawl in the Amazon (SN: 10/23/24; SN: 1/11/24; SN: 5/25/22).

Although the lidar beams that reached the forest floor were not useful for TNC Mexico's tree coverage analysis, they provided valuable data for Auld-Thomas and his team to create a topographic map for archaeological purposes. Reprocessing this data revealed that Valeriana, situated within the broader Maya Lowlands, could have been densely populated. The inhabitants, living in houses encircled by curved, amphitheater-like patios, might have frequented the nearby lagoon or the city's ball court, in addition to participating in rituals at the pyramidal temples.

With over 400 structures per square kilometer, Valeriana's peak building density was more than seven times that of the surrounding region. Only the colossal Lowlands city of Calakmul, near the current Mexico-Guatemala border, had a higher density, with approximately 770 buildings per square kilometer. David Stuart, an anthropologist at the University of Texas at Austin not involved in the study, expressed excitement about quantifying the suspicions that Valeriana could be one of the most densely populated zones of the ancient Maya in the area.

Stuart emphasized that the discovery is not merely about an unknown site but also about understanding how the Maya settled their landscape. Driving through the region, one can observe mounds and pyramids shaping the agricultural fields and ancient agricultural terraces that were once a hub of agricultural activity. The study provides further evidence that the Maya Lowlands were densely populated beyond just Calakmul, which flourished during the Maya Classic period (250-900 AD) and could have housed over 50,000 people. The use of environmental data to uncover this density suggests that previous archaeological research was not an overestimation.

Archaeologist Thomas Garrison of the University of Texas concurs, highlighting the significant strides made in the field with the aid of lidar technology. He notes that this study underscores the value of lidar data for archaeology, even when acquired for different purposes. Lidar data from less-explored regions helps archaeologists assemble a clearer, irrefutable picture of the Maya civilization. However, Garrison points out that the next step involves visiting and excavating these settlements to gain deeper insights.

Source link: https://www.sciencenews.org