Indian tech firms on Wednesday criticized a proposal to reserve over half of all private sector jobs for local hires in Bengaluru, a city that has fueled the nation's rise as an IT giant. Nicknamed India's Silicon Valley, Bengaluru houses Google's national headquarters and those of local tech giants Tata Consulting Services and Infosys. Its IT sector attracts top engineering talent from across the country and contributes nearly a quarter of Karnataka state's estimated $336 billion annual output, according to industry data.

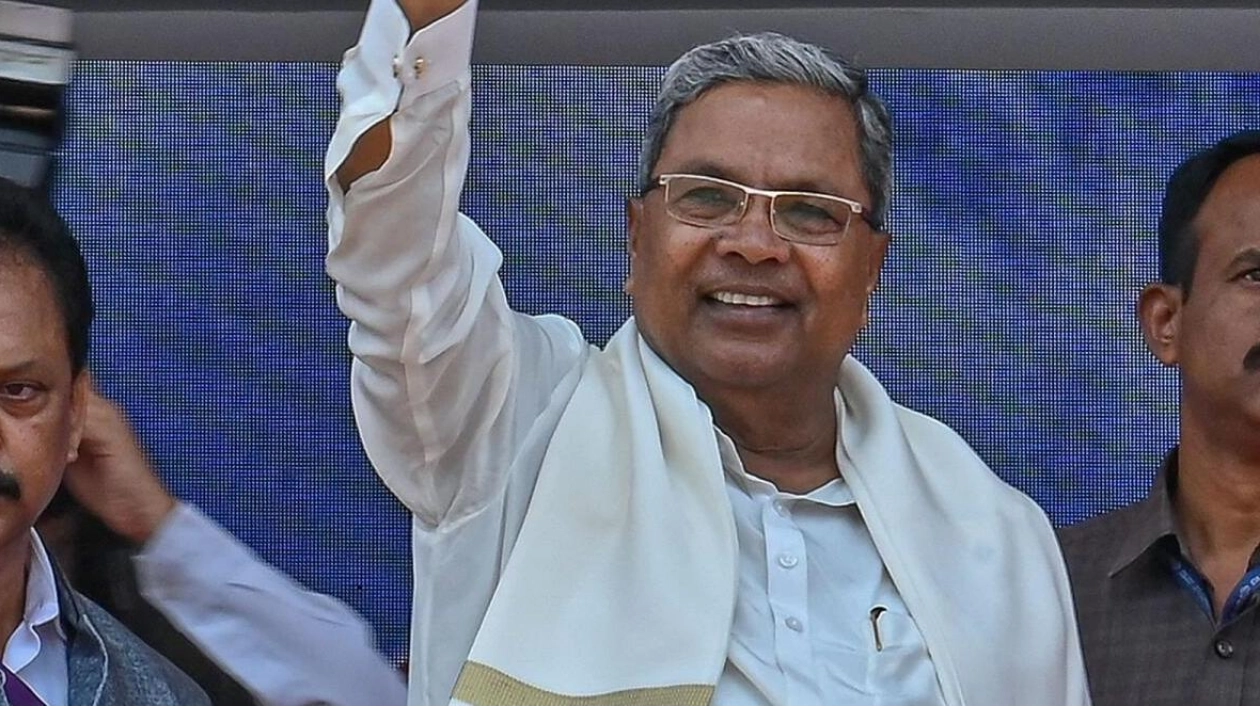

On Wednesday, the state's chief minister, Siddaramaiah, announced that his government was finalizing a new law requiring companies to ensure more than half of their workforce consists of applicants who speak Karnataka's dominant language. Siddaramaiah, who uses one name, stated on X that the initiative aimed to ensure locals were not 'deprived' of jobs and could 'build a comfortable life in the motherland'. The Indian tech industry body, Nasscom, expressed 'serious concern' over the proposal, cautioning that it could disrupt the industry and push out established players.

'It is deeply disturbing to see this kind of bill which will... hamper the growth of the industry, impact jobs and the global brand for the state,' it said in a statement. Other prominent industry figures also criticized the bill, including Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, founder of pharmaceutical giant Biocon, who warned it could jeopardize Bengaluru's 'leading position in technology'. Former Infosys CFO Mohandas Pai called the bill 'discriminatory' and 'regressive'. Nearly 5.5 million people work in IT across India, with many of the most coveted jobs in Bengaluru. However, the influx of Indians from other parts of the country has sparked growing resentment in the city, especially regarding the locally dominant Kannada language.

About two-thirds of Karnataka residents speak Kannada, but the language is rarely used outside the state, with Hindi and English being the common tongues in the city's IT sector. Regionalist activists in the state have previously protested against the use of English on signboards, and Siddaramaiah's government this year mandated that any public signage must be predominantly in Kannada. Linguistic identity tensions are common in India, which boasts hundreds of regional languages. Hindi, the most widely spoken, is a first language for only 40 percent of the population.