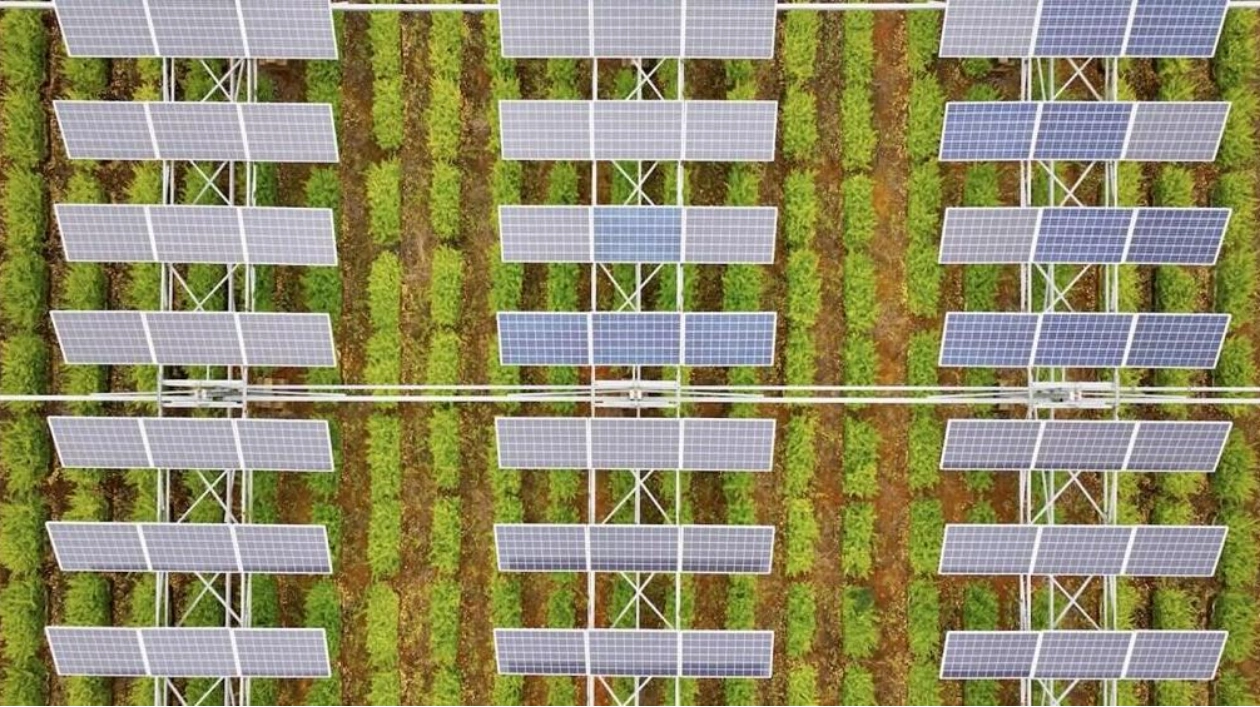

James McCall: Solar production in the US began to gain significant traction around 2012. As solar energy became more mainstream, concerns about land use changes intensified. Ravi Sujith: If we examine the types of land converted for solar installations, over 60 percent of these landscapes were previously used for agriculture. Chong Seok-Choi: Both solar and agricultural activities require flat, sun-drenched areas near transmission infrastructures. Therefore, it is crucial to explore ways to integrate farming and solar power production harmoniously.

Science News is gathering reader questions about navigating our planet's changing climate. What do you want to know about extreme heat and its potential to trigger extreme weather events? McCall: Argivoltaics refers to the co-location of solar and agricultural activities, such as grazing, crop production, and ecological restoration. Sujith: Argivoltaics offers multiple benefits for both farmers and solar developers. McCall: If solar developers can demonstrate that they are maximizing land use, they can access more land for further solar development. Additionally, farmers and landowners can benefit significantly.

Sujith: Even if you lease your land for solar development, you can still engage in income-generating activities like crop cultivation or sheep grazing. McCall: Local communities can also benefit, potentially creating pollinator habitats or prairie restoration. Seok-Choi: Traditionally, people left the ground bare during solar construction, but that practice has changed. Sujith: Covering the land with vegetation can prevent erosion and serve as an opportunity for soil carbon restoration.

McCall: As of July 2024, there are approximately 530 argivoltaic sites in the United States. These sites are divided almost equally between pollinator habitats and solar grazing. Seok-Choi: Currently, there is a strong emphasis on allowing sheep to graze under solar panels, as they do not jump on the panels or chew on wires. Sujith: Integrating sheep grazing can enhance soil nutrients. We recently completed a five-year study in the midwestern U.S., where intense agriculture has led to high carbon depletion. Our findings indicate that managed sheep grazing can improve soil carbon and nutrients.

McCall: If the cost remains the same as mowing grass, and we can provide benefits to local grazers and the environment, why not make it a standard practice? Sujith: There is an emerging consensus that solar grazing holds value in many landscapes. However, there are many unknowns regarding crop production. McCall: Of the 570 argivoltaic sites, only 40 focus on crop production, and most are small-scale research sites. Sujith: The first consideration is determining which crops thrive in specific climates or geographic locations. Some crops may do well under shade, while others may suffer significant yield losses.

McCall: Even two varieties of the same tomato might respond differently to the microclimate created by solar panels. Weather patterns are not consistent, making it challenging to generalize when and where crops would be viable. Seok-Choi: Crop production requires significant modifications in engineering and design. McCall: We need to raise panels high enough to avoid shading or spread them further apart to accommodate traditional farming equipment. These changes come at a cost or reduce energy output, causing hesitancy in the U.S. market.

McCall: We won't implement every system design everywhere, but where and when does it make sense, and why would stakeholders want to do this? With climate changes like reduced water access and increased temperatures, integrating solar becomes necessary. A prime example is wine grape production in California, where current temperatures are too high for certain grape varieties. They are implementing shade structures, so why not also produce solar and generate income from those structures? McCall: There is also a broader need to grow food closer to population centers.

Sujith: We are currently exploring which argivoltaic system configurations are suitable for urban areas. We have set up an experimental system at Temple University's Ambler Campus, which could fit into an abandoned parking lot in a city. The idea is to compare how solar arrays affect crops differently. It might improve yields of leafy greens, potentially allowing an additional cycle of lettuce production. We need to expand the study to other areas to assess different impacts. The next decade will provide much information on various integration types applicable worldwide.

Seok-Choi: That is my dream—being able to point at a map and say, if we put panels here, the climate would change in this way, allowing us to grow this crop. McCall: This is not a one-size-fits-all solution. It requires careful consideration and input from various stakeholders. However, increased solar production can help achieve climate change goals, making it necessary to maximize land use for its highest benefit.

Questions or comments on this article? E-mail us at feedback@sciencenews.org | Reprints FAQ. We are at a critical juncture, and supporting climate journalism is more crucial than ever. Science News and our parent organization, the Society for Science, need your help to enhance environmental literacy and ensure our response to climate change is informed by science. Please subscribe to Science News and add $16 to expand science literacy and understanding.