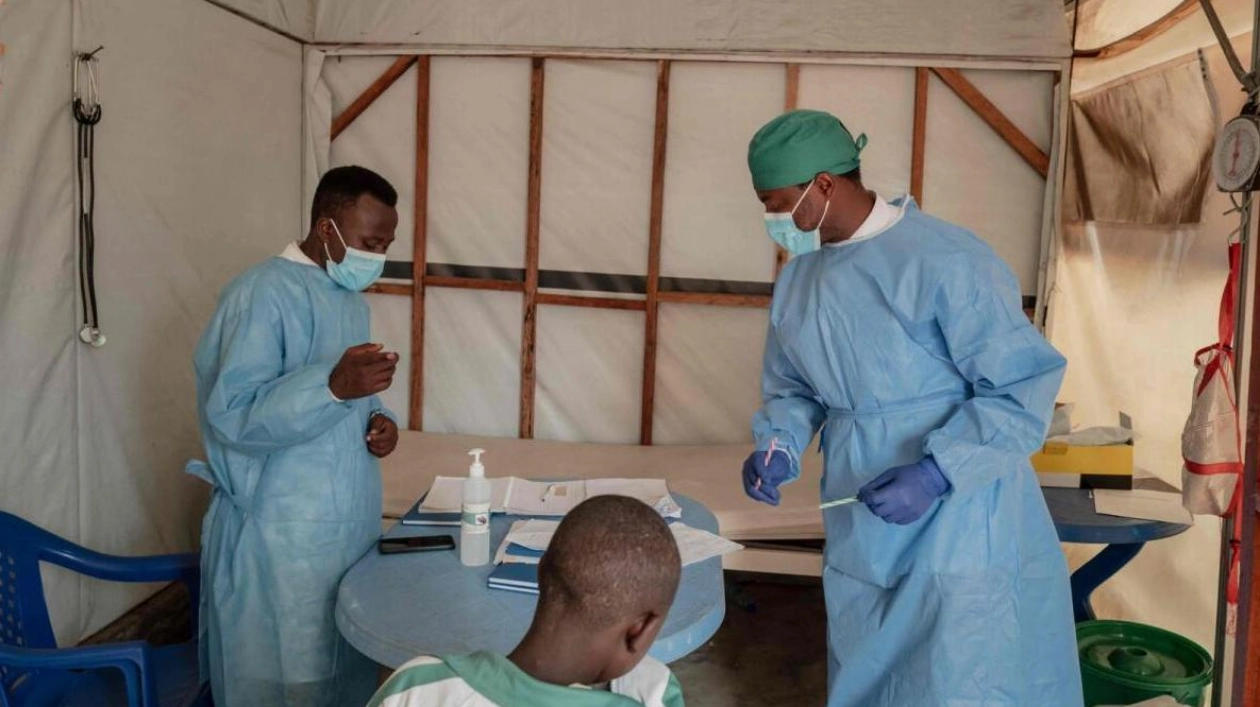

A steadily increasing number of patients are seeking treatment at a hospital in Goma, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, as a swiftly expanding mpox epidemic has taken hold in the region over the past few months. Daily, between five and 20 individuals arrive at Nyiragongo General Referral Hospital in North Kivu, seeking consultation with the overstretched medical staff at an outdoor isolation center, concerned they may have contracted the virus. The disease, which can be transmitted from animals to humans and also between humans through sexual or close physical contact, has claimed 548 lives this year alone. Dr. Tresor Basubi examined a composed young girl with skin lesions caused by the disease, noting that she exhibited no severe symptoms. "This is just the beginning; the child is not weak, she shows no severe symptoms, and she can walk by herself," Basubi remarked during the examination. In most cases, which are generally mild, treatments can alleviate symptoms such as fever with paracetamol and soothe lesions with zinc oxide cream. "Patients experience itchiness, but the scars fade over time," the doctor explained.

Although mpox cases have been reported before, a new, more lethal and contagious strain of the virus, known as clade 1b, has a mortality rate of approximately 3.6 percent, with infants and children at greater risk, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). The DRC, with around 16,000 cases recorded this year, is at the heart of this epidemic, prompting the WHO to activate its highest level of international alert on Wednesday. In the neighboring province of South Kivu, approximately 350 new cases are detected weekly, according to epidemiologist Justin Bengehya. Goma, the capital of North Kivu, surrounded by armed conflict and home to hundreds of thousands of displaced people in temporary camps, is particularly vulnerable to widespread transmission due to overcrowding. At the treatment center, parents held their infected children, despite the risk of skin-to-skin transmission, while staff educated them on prevention measures.

Deogracias Mahombi Sekabanza, a health worker, recounted how his son was hospitalized with mpox and his daughter contracted the disease after caring for him. Furaha Makambo, living in a tent with her three children who all contracted mpox in the camp, expressed her fear: "We are scared, this disease needs to be eradicated so that it stops reaching the displaced because it can exterminate us." Despite preventive measures and past epidemic experience aiding staff in swiftly responding to suspected cases, social distancing remains challenging for children. "This disease is very contagious. If you touch the sweat, urine, or even clothes of a sick person, you are directly exposed," warned Dr. Basubi. "Washing hands with soap or ashes can help protect you, but there is no guarantee," he added. Nyota Mukobelwa, a displaced doughnut vendor, emphasized the need for vaccines: "The vaccine needs to be available, otherwise the epidemic will continue to spread, many people will die, and we will contaminate our children at home." The WHO has called on manufacturers to increase mpox vaccine production and urged countries to donate their stockpiles to countries experiencing outbreaks.