Fifty years ago, in a corner of white South Africa, Muhammad Ali was already perceived as a miracle-maker. In our strictly regimented and divided nation, Ali danced rings around apartheid. My first encounter with the inspirational boxer was through a black man named Cassius, who sold beer from an illegal shebeen across the road from our house. Cassius and his friends kept their illicit stash hidden in the drains outside a corner shop owned by an irritable Greek man. Whenever my football landed over the garden wall, Cassius would chase after it, showcasing his slightly drunken footwork before returning the ball with a cackle. One day, while demonstrating his trickery, he sang a peculiar song: “Ali, Ali, float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, Ali, Ali, Muhammad Ali.” As he flicked rangy left jabs into the winter sunshine, his huge feet danced in a pair of battered brown sandals. He pretended to be outraged when I asked who he was singing about: “You mean the baasie [Afrikaans for little boss] don’t know?” When I shook my head, he became serious: “Ali is the heavyweight champion of the world.” A thrill surged through me as Cassius explained how he was nicknamed after Ali, who was born as Cassius Clay. I struggled to comprehend how one man could have two names. Cassius elaborated that the master boxer was a black American who coined those joyful bee and butterfly lines.

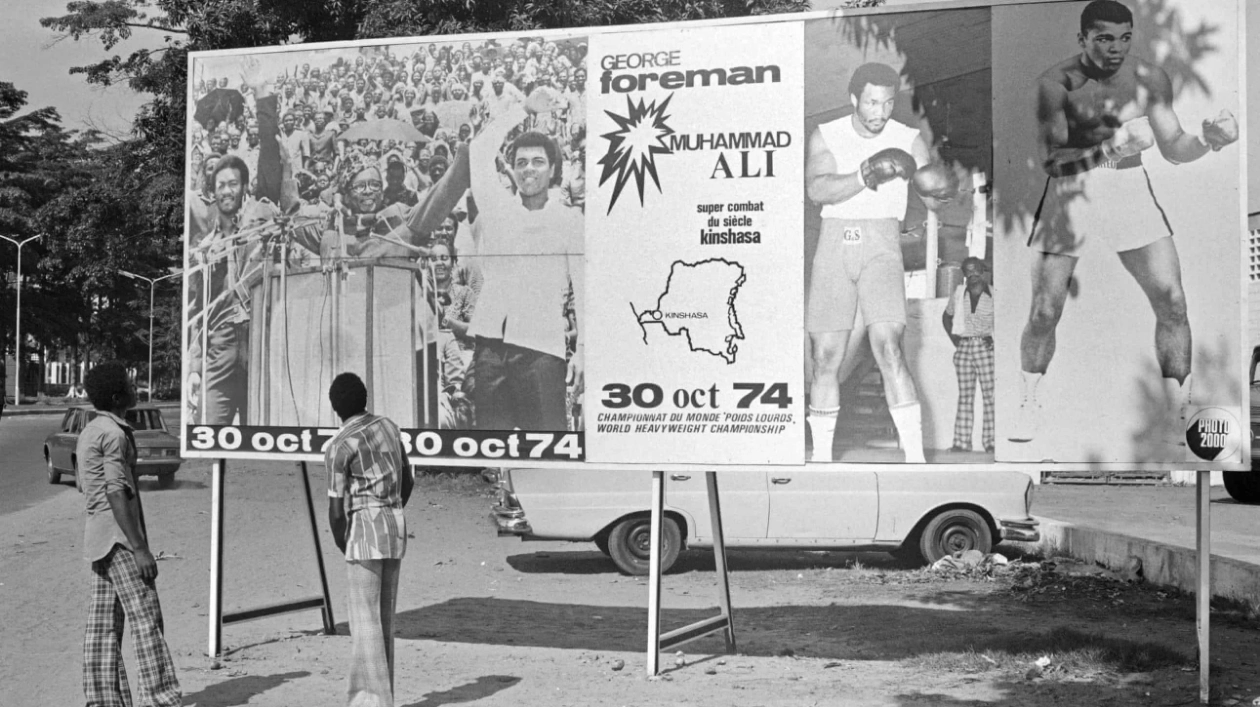

Years later, in 1974, when I had just turned 13, I learned that Ali had been stripped of his world title in 1967 for refusing to fight in the Vietnam war. Yet, he became even more of a mythical figure to me as he enchanted our intimidating Afrikaans teacher with the same charm he had over Cassius. When we mustered the courage to ask the teacher why he admired Ali so much, despite suspecting he was a staunch racist, the teacher softened. He spoke of the beauty and brilliance of Ali in the ring, describing him as more than “one of our blacks”—Ali was the king of the world. On 30 October 1974, Ali finally had a chance to reclaim the title when he faced George Foreman. We were agog that the fight would take place not far from us, in Zaire [now the Democratic Republic of Congo]. The Rumble in the Jungle was promoted by Don King, who showcased his ingenuity by bringing the bout “back to Africa.” Zaire’s dictatorial President, Mobutu Sese Seko, agreed to pay the boxers an unprecedented $10m each. Although the rest of Africa felt distant from our privileged suburb near Johannesburg, King brought the continent into our classrooms. Other kinder teachers confessed their fondness for Ali and favored him over Foreman. Ali was also hailed by the black cleaners and gardeners who serviced the school and our homes. And the shebeen corner—from the Greek shop owner to the biggest drinkers—still belonged to him. Only Ali could forge such an alliance.

No heavyweight was bigger or more threatening than Foreman, who had become world champion by demolishing Joe Frazier in two rounds. Frazier, who had beaten Ali in the Fight of the Century in 1971, was blown away by Foreman, who had a 40-0 record with 38 stoppages. Big George rained down bludgeoning punches, bringing sorrow to every fighter he faced. Only the 32-year-old Ali remained. “Foreman by knockout,” I predicted mournfully, fearing so much for Ali. A quick knockout would save him from permanent damage. But Bennie da Silva, my friend’s dad and the only real boxing expert we knew, backed Ali. He was a stocky Portuguese man who made us laugh while flooring us with his ring knowledge. He promised that Ali would dance the night away until Foreman was so dizzy he wouldn’t know what hit him. Ali would rumba through the rumble and be crowned world champion again. Television was still banned in South Africa as the government regarded it as a tool of communist propaganda. So we could not watch the fight in the early hours of a spring morning. But we listened to games of English football on the BBC World Service every Saturday afternoon, meaning our schoolyard was packed with staunch followers of Arsenal and Liverpool, Leeds and Manchester United. My dad helped me tune into the BBC radio broadcast, and in bed, I trembled as Ali went into battle with the ogre. But I was stunned as, in the crackle and hiss of the wireless, Ali did not do the rumba. He simply refused to dance. He not only stood still but, in an act of supposed madness, leaned against the ropes and allowed Foreman to hit him. Ali took every ruinous blow and still he stood, waving his man in and doing the “rope-a-dope” trick we would try to copy at school. Then, as if he was as exultant as Cassius on the corner or Mr da Silva boxing in the kitchen, Ali began to pick off Foreman. Through the static and electrifying commentary, it sounded like Ali was weaving a new kind of black magic. Abruptly, near the end of the eighth round, it was all over. A cry reverberated from the tiny speaker, as penetrating as any factory siren: “Foreman is down! Foreman is down!” I tumbled in disbelief, wondering if there could be as much bliss in the hearts of Cassius and the scary Afrikaans teacher, wherever they were that memorable daybreak. Ali, truly, was the king of the world, and we felt proud that his coronation happened in Africa—from where, at last, we knew we really belonged.

Source link: https://www.theguardian.com