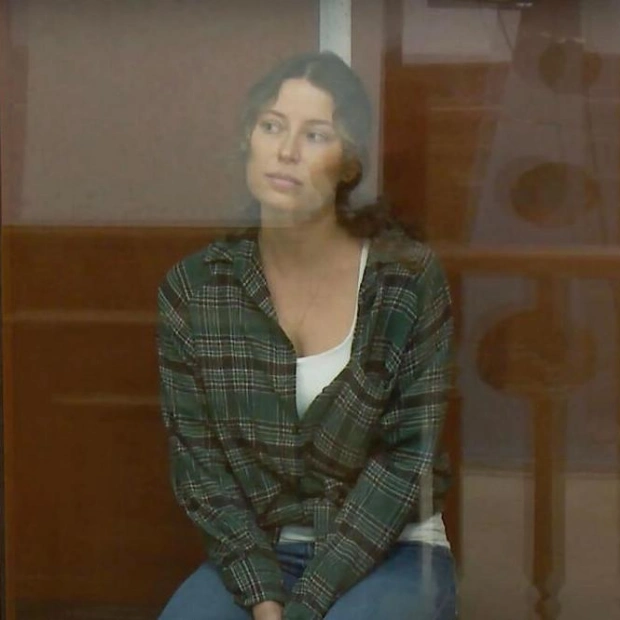

Marita Blanco, who collects plastic bottles, styrofoam, and candy wrappers for two pesos (3.4 US cents) per kilogram, resells them at a 25 percent markup to the US charity Friends of Hope as part of its waste-to-cash program. She operates her weighing machine near a shipping container in Manila. – AFP

The Philippines, long one of the world's top sources of ocean plastic, is banking on new legislation requiring big companies to fund waste solutions to clean up its act. Last year, the country introduced its 'Extended Producer Responsibility' statute—the first in Southeast Asia to penalize companies for plastic waste. This initiative has demonstrated both potential and challenges, which could be part of a global treaty on plastic pollution countries aim to agree on this year.

With a population of 120 million, the Philippines generates around 1.7 million metric tonnes of post-consumer plastic waste annually, according to the World Bank. A third of this waste ends up in landfills and dumpsites, while 35 percent is discarded on open land. The EPR law aims for 'plastic neutrality' by compelling large businesses to reduce plastic pollution through product design and waste removal. Companies must initially cover 20 percent of their plastic packaging footprint, a figure that will rise to 80 percent by 2028. The law covers various plastics, including flexible types often deemed commercially unviable for recycling.

So far, about half of the eligible companies have launched EPR programs. Over a thousand more must comply by the end of December or face fines up to 20 million pesos ($343,000) and potential license revocation. The law removed 486,000 tonnes of plastic waste last year, exceeding the 2023 target and contributing to a broader strategy to mitigate the environmental impact of plastic pollution.

Companies can outsource their obligations to 'producer responsibility organizations', many using plastic credits. These credits allow firms to purchase certificates indicating a metric ton of plastic has been removed and processed. PCX Solutions, a major player, offers credits ranging from $100 for mixed plastic collection and co-processing to over $500 for ocean-bound PET plastic collection and recycling. This model aims to boost the underfunded waste collection sector and encourage the collection of plastics not commercially viable for recycling.

Former streetsweeper Marita Blanco, a widowed mother of five from Manila's low-income San Andres district, sees this as a financial boon. She buys plastic waste for two pesos per kilogram and sells it at a 25 percent markup to Friends of Hope, which partners with PCX Solutions. 'I didn't know that there was money in garbage,' she said, adding that her financial situation will improve if she continues this work.

Friends of Hope's managing director, Ilusion Farias, notes the project's visible impact on an area typically littered with plastic. 'Two years ago, I think you would have seen a lot dirtier street,' she said, acknowledging the slow pace of behavioral change.

Snack producer Mondelez is among those purchasing credits, opting to offset 100 percent of its plastic footprint. 'It costs company budgets... but that's really something that we just said we would commit to do for the environment,' said Mondelez Philippines corporate and government affairs official Caitlin Punzalan.

While companies have embraced plastic credits, efforts to reduce new plastic production through redesign have lagged. 'Upstream reduction is not really easy,' said PCX Solutions managing director Stefanie Beitien. 'There is no procurement department in the world that accepts a 20 percent higher packaging price just because it's the right thing to do.'

Despite the law's limitations, such as allowing waste burning for energy, it remains a 'very strong policy', according to Floradema Eleazar of the UN Development Programme. However, 'we will not see immediate impacts right now, or tomorrow,' she said, emphasizing the need for widespread behavioral change.

Source link: https://www.khaleejtimes.com