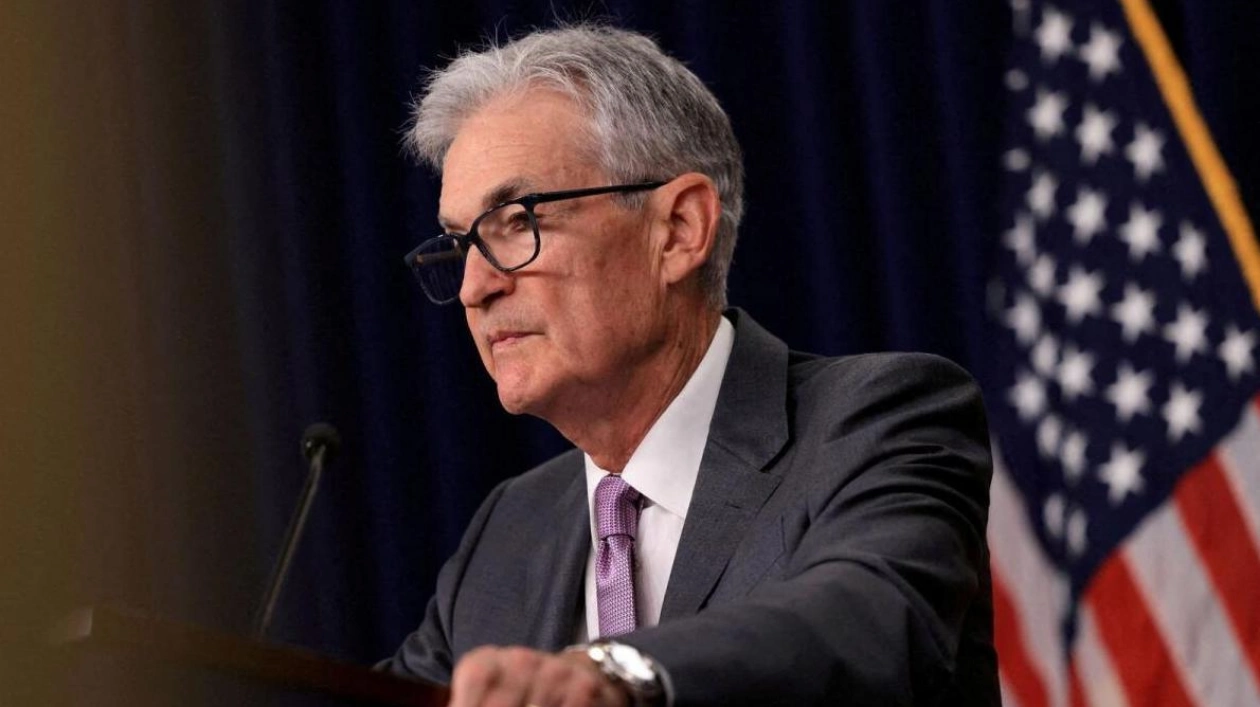

Four years after Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell prioritized combating unemployment during the Covid-19 pandemic, he now confronts a critical test of that focus as joblessness rises, evidence accumulates that inflation is contained, and a benchmark interest rate remains at its highest level in a quarter of a century. High interest rates might soon be reduced, with the US central bank anticipated to make the first cut at its September 17-18 meeting, and Powell possibly offering further details on the policy easing approach in a speech on Friday at the Kansas City Fed’s annual conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. However, with the Fed’s policy rate hovering between 5.25% and 5.50% for over a year, the lingering effects of high borrowing costs on the economy could continue to grow and might take time to reverse even if the central bank begins to cut rates—a scenario that could jeopardize hopes for a “soft landing” with controlled inflation and sustained low unemployment.

“Powell asserts that the labor market is normalizing,” with wage growth moderating, job openings remaining robust, and unemployment near levels that policymakers believe align with the central bank’s 2% inflation target, according to former Chicago Fed President Charles Evans. “That would be excellent if that’s all there is. The historical record is not encouraging.” Indeed, increases in the unemployment rate, such as those observed in recent months, usually lead to further rises. “That doesn’t appear to be the case now. But you might be just one or two poor employment reports away” from needing aggressive rate cuts to counteract rising joblessness, Evans noted. “The longer you delay, the more difficult the actual adjustment becomes.”

Evans played a crucial role in reshaping the Fed’s policy approach, which Powell unveiled at Jackson Hole in August 2020 amid the pandemic, with policymakers convening via video and the unemployment rate at 8.4%, down from 14.8% in April. In this context, the Fed’s shift appeared logical, altering a long-standing inclination to curb inflation at the expense of what policymakers began to see as an unnecessary burden on the job market. Traditional monetary policy saw inflation and unemployment as inherently and inversely linked: low unemployment fueled wages and prices, while weak inflation indicated a stagnant job market. Officials started rethinking this connection following the 2007-2009 recession, concluding that low unemployment didn’t inherently pose an inflation risk.

As a matter of fairness for those at the margins of the job market and to achieve optimal outcomes overall, the new strategy stated that Fed policy would “be guided by assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level.” “This change might seem subtle,” Powell said in his 2020 speech to the conference. “But it reflects our belief that a strong job market can be maintained without triggering an outbreak of inflation.” A pandemic-driven inflation surge and a dramatic employment recovery initially made this change seem irrelevant: the Fed had to raise rates to curb inflation, and until recently, the pace of price increases had slowed without significantly impacting the job market. The unemployment rate had been below 4% for over two years, a streak unmatched since the 1960s. The average unemployment rate since 1948 has been 5.7%.

However, the events of the past two years and an upcoming Fed strategy review have sparked a surge of research into what exactly transpired: why inflation declined, the role of policy in that outcome, and how future approaches might differ if inflation risks resurface. Although the agenda for this year’s conference remains undisclosed, the broad theme centers on how monetary policy affects the economy. This impacts how officials might assess future choices and trade-offs and the wisdom of tactics like preempting inflation before it begins. Some of this work is already emerging from Fed researchers, including chief economist Michael Kiley, who has questioned whether policy “asymmetry”—treating employment shortfalls differently from a tight labor market—truly aids. Another recent paper suggested that policymakers who believe public inflation expectations are short-term and volatile should react more swiftly and raise rates more aggressively in response.

The role of public expectations in driving inflation—and the policy response—was evident in 2022. When it seemed that expectations might escalate, the Fed accelerated its tightening cycle with 75-basis-point hikes at four consecutive meetings. Powell then used a condensed Jackson Hole speech to underscore his commitment to fighting inflation—a significant shift from his earlier focus on jobs. This was a pivotal moment that demonstrated the US central bank’s seriousness, bolstered its credibility with the public and markets, and restored some of the standing that preemptive policies had lost. ‘Too tight’ Powell now faces a different test. Inflation is moving back towards 2%, but the unemployment rate has climbed to 4.3%, an increase of eight-tenths of a percentage point from July 2023. There’s debate about what this truly signifies for the labor market versus rising labor supply, which would be positive if new job seekers find employment. However, it did breach a rule-of-thumb recession indicator, and while other indicators suggest a growing economy, it is slightly above the 4.2% that Fed officials consider indicative of full employment. It’s also higher than at any point during Powell’s pre-pandemic tenure: it was 4.1% and declining when he assumed leadership in February 2018.

The “shortfall” in employment that he pledged to address four years ago may already be materializing. While Powell will be cautious about declaring victory over inflation to avoid triggering an exuberant overreaction, Ed Al-Hussainy, senior global rates strategist at Columbia Threadneedle Investments, argued that it’s high time for the Fed to address the risk to unemployment—a different form of preemption. Al-Hussainy noted that the Fed has demonstrated its capability to manage public expectations about inflation, an important asset, but that “also introduces some downside risk to employment.” “The current policy stance is offside—it’s too tight—and that necessitates action.”