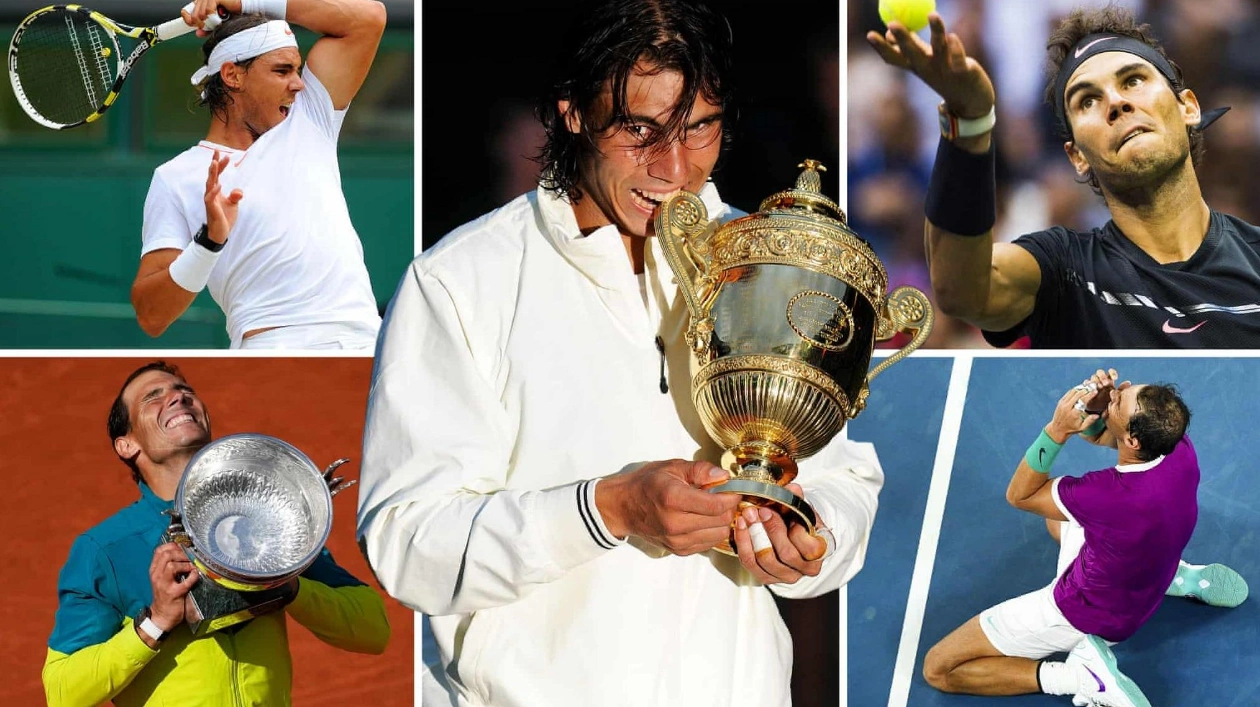

Elite sport is a unique blend of ritual, repetition, ingrained habits, honed skills, acknowledged strengths, and dreaded limitations. However, passion is indispensable – and sometimes, even that is insufficient. At 38 years old and in reasonably good shape, Rafael Nadal mustered all these elements as best as he could during his final match in Málaga on Tuesday night, but his efforts were not enough to secure a victory in his farewell. He faced defeat in his last match with the same dignity he displayed in his first win at the age of 15. Yet, he lost, and it pained him deeply. He wouldn't have had it any other way.

Now, he can finally leave behind the grueling routines and processes. No more hours spent sweating in the gym, adjusting his shorts, tugging at his headband, or wiping his brow with his wristbands. No more meticulously arranging water bottles at his courtside chair or waiting for the draw or a call from one of his numerous doctors. At last, he can indulge in his hobbies, such as golf and fishing, relax under the Spanish island sun, and be free from the privileges and pressures that come with being a genius.

Nadal, one of the most gracious champions I have had the pleasure of knowing, will depart from his sport feeling fulfilled yet frustrated by the manner of his exit. He gave everything he had in his final career match against Botic van de Zandschulp, a straightforward hitter who is the Netherlands' No. 2 and world No. 80, in the Davis Cup quarter-finals. Nadal needed more than just the support of the Spanish crowd to overcome an opponent who had previously defeated his young compatriot, Carlos Alcaraz, at the US Open. The brilliant moments he conjured in their two sets in Málaga were like fleeting sparks of a dying flame.

At least he wasn't facing an opponent like Jake Paul. He managed to unleash his shots when he could. However, too many of his 26 attempts missed their mark. He had his opportunities but couldn't capitalize on them. Like Tyson, he had made others pay dearly during his prime, but that time has passed. 'The crowd was tough,' the winner acknowledged. 'Understandable. If I were in the crowd, I'd be cheering for him too.'

Who didn't want Nadal to achieve one more victory? I'll soon forget the 6-4, 6-4 score. Other memories will remain etched forever. In 2008, the Spanish newspaper Marca sought someone to provide an extra preview of the Wimbledon final between Nadal and Roger Federer. 'Who do you think will win?' their correspondent asked me in the press room just before one of the greatest matches of all time. 'Nadal,' I replied, eyeing a few extra Euros. The gig was mine.

From that epic five-set win until now, my professional objectivity has been stretched to its limits. Nadal, in Bob Dylan's words, was 'forever young.' Or at least he aspired to be. Before facing Andrey Rublev in the 2017 US Open quarter-finals, I asked him if he remembered what it was like to be that age. 'Rublev is 19?' he replied. 'If I could return to 19, I'd take it. When you're young, you have many more years to enjoy the tour and life. Of course, it's better to be 19.' He paused and added, 'I always wanted to be young. Even when I was eight, I wasn't very happy about turning nine. I'm still the same. I'm 31, and I'm not happy about turning 32. I'm happy being young, right? I don't want to get older. For now, I haven't found a way to stop that clock.'

He would mercilessly defeat Rublev 6-1, 6-2, 6-2, followed by Juan Martin del Potro and Kevin Anderson in the final to claim one of his 22 major titles. Seven years later, his hair has thinned, his feet have slowed, and his muscles ripple less convincingly. In the harsh judgment of his sport, he is old and done. But what a life, what a career.

Nadal has always been remarkably honest, often in a second or third language, which he embellished with naivety and unintended humor. For many years, he pronounced 'doubts' as 'doobts' until, to the annoyance of those who teased him with mischievous questioning, a British tennis writer corrected him. I hope Rafa never thought we were being cruel behind his back. We weren't. He was universally beloved in the press box.

Nadal and Federer were good friends but fierce rivals. The same was true for the third member of their triumvirate, Novak Djokovic. They all transformed into ruthless competitors when it mattered most, elevating their game to unprecedented levels of excellence. What Nadal valued more than others' opinions was, as he called it, 'the real thing.' Nothing captivated him more than the unavoidable reality of the court. He was immune to the concerns of the smart writers and, occasionally, the crowd. He rarely smiled during a match, although afterward, his ever-bright face would light up any room.

When the notoriously rowdy Monte Carlo patrons booed him for a disputed line call during his 2017 semi-final against David Goffin, Nadal held no grudge, describing their behavior as merely sad. He later revealed that in the shower after the match, he and Goffin never mentioned the controversy that cost the Belgian a 4-2 lead in the first set – and possibly a famous victory – something the wealthy tax dodgers sipping champagne on the country club's terrace overlooking Court Central that afternoon would struggle to comprehend. They were professional drunks; Nadal and Goffin were professional athletes.

When Nadal announced his retirement last month, it was with similar calm resignation. 'I cannot be competitive enough,' he said. 'The question to myself is: 'OK, I can go one more year, but why?' To say goodbye in every single tournament? I don't have that ego. The end is about a feeling I've been contemplating for a long time. My body is not capable of it now.' Nor was his spirit. The passion that had been so strong for so long had waned beyond usefulness. Inevitably, the tributes poured in. Federer, who won their final encounter at Wimbledon five years ago at the age of 37, remembered it was a 17-year-old Nadal who won their first meeting in 2004. 'I thought I was on top of the world,' he said of that match. 'And I was – until you walked onto the court in Miami in your red sleeveless shirt, showing off those biceps, and you beat me convincingly.'

Federer won 16 of their matches and lost 24. So, who was the greater or the greatest? Does it matter? To some. Maybe to Federer. Certainly to Djokovic. But, beyond argument, not to the humble man from Mallorca who will be busy this winter working on his +0.3 handicap at the nearby Pula golf club.

Source link: https://www.theguardian.com