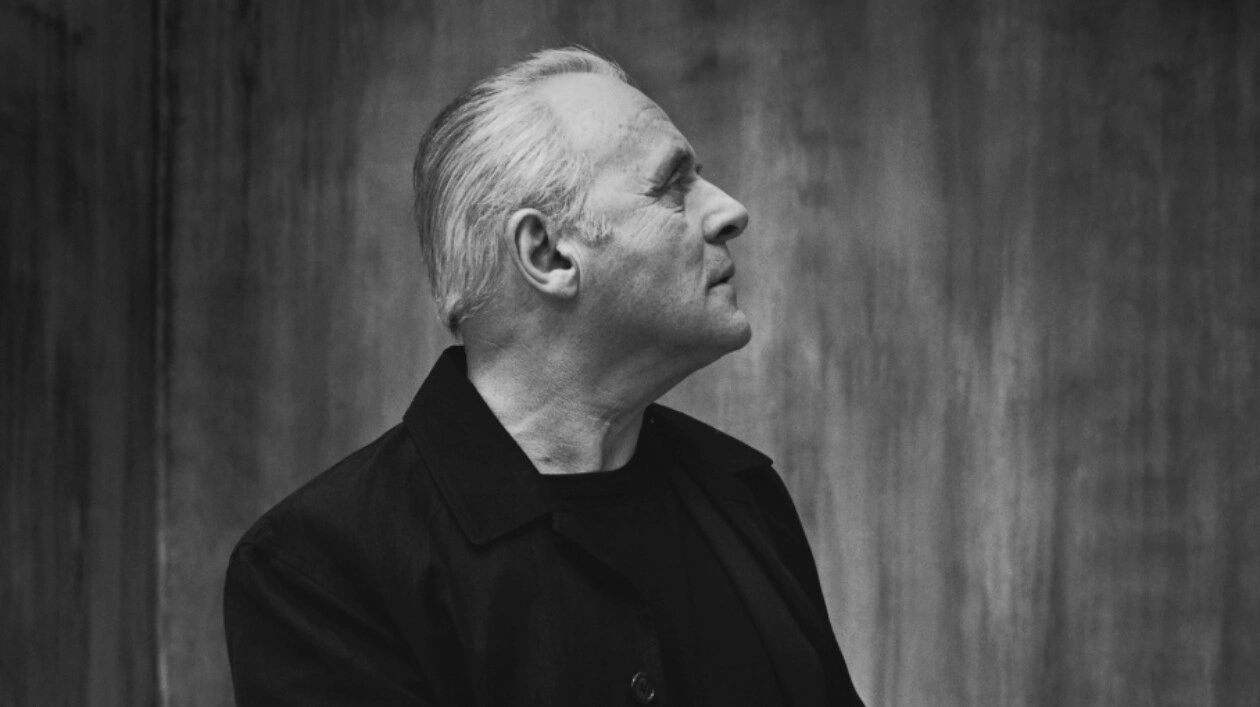

With his mind at peace and his spirit well-balanced, he is able to watch the world and humanity from a meta-position as well as see his father in himself. In this genius’s words, you cannot but feel genuine kindness and warmth towards each and every one he mentions. In an interview with Nellee Holmes, a Golden Globe Awards voter and our Hollywood correspondent, the brilliant play actor dwells on wisdom, zen, the succession of generations, the finitude of being, the film stars of today and the days long gone, the certainty of death, and the pleasure life can afford.

Nellee Holmes: Tony, so good to see you. First of all, I’d like to ask you about your birthday.

Anthony Hopkins: I was born on 31st December — New Year’s Eve. I am not a good party boy, you know. I used to celebrate my B-day when I was younger, but I don’t think I can remember the last time I did it. I’ve already had my 60th, 70th, 80th birthdays, so I make no big deal of it anymore. It’s just another day. Next time, I’ll turn 86 and, maybe, blow out a candle. I’ve had 85 of them by now, so it’s no big deal for me.

N.H.: ‘The Father’ — one incredible, unbelievable, and brilliant performance! Watching it, I could not help wondering, ‘Dreams. Confusion. Illusions. What’s real, and what’s not?’ Could you explain what the word ‘illusion’ means to you?

A.H.: Well, it wasn’t a difficult part for me to play — not at all. As I’m getting older, I look back at my life, and it all seems to be a bit of an illusion — as if somebody else wrote a script for me to act out. I don’t know how my life has unfolded, in a way, beyond my control and knowledge. Therefore, strangely enough, I cannot take credit for any part of it. Looking back, everything seems to be just an illusion — mystical, as it may sound. I look back and ask myself, ‘How did any of that happen?’ We go through life, and life is tough. Still, I’ve been very fortunate, you know. People die — my mother, father, and grandparents are gone. Many individuals I once knew well have also died, but I’m still here — 85 years of age, looking back and thinking, ‘How did I get here? How have I survived all these years, and yet I have so much of me?’ Isn’t it elusive? This may sound really weird, but that’s what it feels like to me.

It feels like a long story of somebody else’s life, just like my part in ‘The Father’ — Florian Zeller’s first film. He’d never directed films before. He’s just amazing! He’d written the original play. Then, Christopher Hampton wrote the screenplay, and Florian directed it. It was great to work withFlorian Zeller, Olivia Colman, Olivia Williams, Rufus Sewell, and everyone else involved. It was easy because I’m of that age now.

I’ve forgotten what I was going to say, but what particularly struck me when I saw the film was my father in me — on the screen, I am my father’s copy! I didn’t even know it. I didn’t consciously play that way. But looking at it, I think, ‘That’s my old man! That’s my father!’ He could be pretty tough, belligerent, and argumentative. I thought over the years, I’d learnt to calm down that side of my nature, but it was my father in me no doubt! I remember the last scene of the film. Just before we started shooting it, I was looking at the chair I’d used to sit on and the glasses, lying on the table, and remembered my father — he died while picking up his reading glasses and the book he’d been reading. At that moment, I thought, ‘God, did he ever exist?’ Does any one of us really exist? I don’t know. It’s all such a mystery to me.

Oddly enough, I found some strange peace in this idea, you know. My parents didn’t suffer from dementia. I don’t think they did even though my father did suffer from depression till the very end. He had a year of decline from his heart disease and became quite belligerent with me. Maybe, because I represented something, awaiting me some years ahead. He was very depressed. I understood I was looking at that from the past, thinking to myself, ‘That’s what my father was, and that’s what it must be like’.

Now, I read a lot, paint, and play the piano five days a week. I play complicated stuff. Not because I want to play in Carnegie Hall — far from it! I do it because it keeps my brain active. I memorise things so that I can keep my memory facility going, you know.

So far, I’ve experienced what dementia is like only in one case. One day, a friend of mine from New York City — the father of the family — looking out the window of his son-in-law’s house in Palisades, here in California, suddenly said, ‘The Hudson’s looking very wide tonight’. Well, he thought the Pacific was the Hudson. I could see the way it affected his family, his son-in-law, his wife, and his daughter. Great was the pain they went through, having to explain things to him! And in the end, he’d just sit there and drink his coffee very peacefully, not knowing who was around him. I thought, ‘What a strange world it must be!’ On the other hand, it’s, kind of, comforting — maybe, it’s a way of nature’s shutting down one’s life.

N.H.: We often forget that our physical bodies are not machines. They need rest and lots of care. Healthy minds in healthy bodies help us be more productive and achieve better results both at work and in our personal lives. What do you do to improve your wellness and restore the balance of mind and body?

A.H.: Well, I was born strong and have always been pretty strong and muscular. It’s my Welsh background, I guess. I work out five days a week on a treadmill in the gym, do some weights — not too strenuously, you know — and keep as flexible as I can. I also read a lot and practise meditation. And, you know, I stay cheerful even when dark moods come upon me — they sometimes do in every human’s life. At such moments, you can’t but think, ‘Is there a way out?’ But that’s the way human life is, and we’ve got to accept the fact. I don’t want to sound mushy, but I do say ‘Thank you!’ for whatever given to me in my life — especially in the tough business I’ve been in. I came to America many years ago and have been given a great life here. So, I feel appreciation and gratitude for what I’ve got. I’m not, you know, a saint or anything like that. I’m only human, but I do remember that I am very lucky to have lived such a long life and feel very grateful for that. You come to it gradually and in a strange way, you know.

There’s always been a lot of pain and suffering in the world. I still remember England and Wales in the post-war years. I was born just before World War II, and its last years are still alive in my memory although we didn’t suffer much, you know. The cities around were bombed. There was a dark depression after the war, but we pulled through nonetheless. I think what has always kept me going is having a perspective. I watch documentary films — I’m, kind of, obsessed about it — showing post-war Europe. God! Devastation, horrors, millions of deaths! I look at our world today and think, ‘Well, yeah! Things are tough sometimes, and we go through strange times, but we can survive! Here in America — the powerful nation that it is — we will survive!’ So, I think it’s the feeling of gratitude and appreciation that keeps me healthy. Well, it’s been a long answer.

N.H.: You are also a very talented artist. What have you been painting lately? Has your focus changed over the years? Have you changed your manner of painting in any way? What are you working on now?

A.H.: Well, I seem to paint an endless array of faces and eyes. I don’t try to change anything much. I am not a trained painter, so having no academic background, I just improvise — I go into my very small studio, put up a canvas, and start painting. I never plan it but just put the paint on the canvas, form an image, and carve something out of it, having no clue what I’m doing.

A friend of mine, the late Stan Winston, the designer of ‘Jurassic Park’, was a bona fide artist and a trained one too. Many years ago, when I just started painting, he came over to my house for a barbecue — I was living in Malibu then — and went into my studio to use the bathroom. He looked up at the wall and asked, ‘Who did these paintings?’ I pulled a face and said it was me. He wondered, ‘Why are you pulling a face like that?’ I answered, ‘Well, I’ve never had any training’. To which, he replied, ‘Don’t! Don’t train. Just paint’. That’s exactly what he said, and that’s exactly what I do, also following author Henry Miller’s advice, ‘Paint and die happy!’

I paint for no special goal, but my pictures sell. I have shows up in Vegas and Hawaii, and people buy my works. I love colours. At the moment, I’m experimenting with a wide range of them to make these Hispanic paintings, you know, showing the colours of Colombia. My wife Stella comes from Colombia, and I’m going to send one to her brother to see if he approves it. I don’t have any form or style — I just experiment. Every now and then, I give away a few paintings, and people seem to enjoy them. That’s how it is. I don’t plan it. I don’t think it over. I don’t think about it very much actually.

N.H.: Olivia Colman says she has a great short-term memory, but the next day after the shoot, she has no idea what she said the day before. I think, in a way, you’ve had the same intuitive manner of acting throughout your entire career. What was it like working with Olivia, who, in a sense, is very similar to you?

A.H.: Oh, she was wonderful to work with. The whole cast was, you know — it wasn’t large, but all the actors were excellent. She’s very much like ... I have to be careful using words — she didn’t take it too seriously. She’s so good, and she is like me. I mean, when you’ve been around a bit of time, one day, you get to a point when you just don’t make a big deal of it anymore. I’m much older than Olivia, but I think we are very much alike.

I consider the script I get to be a road map. I’ve been asked if we just learn the lines. Well, yes, in a way. The script is like a guide from outer space for a car driver. What do you call these navigation things? — I don’t know. In the old days, we had road maps to follow. Going from here to Las Vegas or Phoenix, you follow a route, and, you know, every so often, you want to take a little side road. You don’t have to analyse the map. You just follow it. The script is pretty much the same. You get a really great screenplay, a script, a play, or whatever it may be by Christopher Hampton, Florian Zeller, Tennessee Williams, William Shakespeare, or whoever else, and you just follow this ‘road map’ and ‘drive along this route’. En route, you look at ‘sideways, little byways, and side roads’, thinking, ‘I’ll go this way and slightly reinterpret it, although without rewriting it’.

I’ll give you an example. It was the very first day — a Monday morning — of filming and the very first scene Olivia and I had together. Without rehears- ing, we just did a walk through it, you know. Florian was there with us while we were doing all that and said, ‘Okay, let’s have a go at it. Everything okay? Yeah. Do it. Action! Good’.

Let’s do one more, and you’ll see how easy it is if you just listen. Laurette Taylor — a great American stage actress — once said, ‘The art of acting is lis- tening’. And for a fact, it is. If you listen to the other person as they’re speaking, it’s as if you’re hearing it for the first time, so it keeps it fresh. You have to listen — that’s the only way.

In an interview about ‘The Bridges of Madison County’ with Clint Eastwood as a journalist, Meryl Streep was asked if it took a lot of intense concentration, and her answer was, indeed, very interesting — she said, ‘No, intensity is the last thing you need’. That’s true — you have to loosen up, you know, and just learn your stuff. That’s what I do.

Watching ‘The Father’ a few weeks ago, I felt so pleased as I’d forgotten how I’d got all that and didn’t remember taking all those courses in this and that. What was reflected back to me was the fact that I had actually worked meticulously on learning the lines so well over and over again. As long as you do your homework — which you have to, your preparation being learning your lines — it becomes your second nature. You don’t have to think about it, so when another line and the other person come in, your brain automatically takes over and improvises in a realistic way. When you’re younger, you want to become very real and intense, and that’s all right. Then, you reach a certain age and think, ‘Oh, well, I’m a fan of those great guys like William Holden or Robert Mitchum’. So, you just let it roll off you and don’t take it all so seriously — that makes the whole thing easier. Now that I’ve met Robert Mitchum in person, they’re an example of just making it look easy.

N.H.: I know your wife Stella very well. It’s fantastic that she wrote a script and directed a film you acted in, playing a doctor, which is the opposite of what you do in this film — you must be a natural psychologist. I’d like to ask you about this experience of working with Stella.

A.H.: She was an excellent director, even though it was her first time. She’d written the script and directed everyone. I mean, it was really quite remarkable. And it was easy. It’s a fine film, in which I play a psychiatrist, with a good cast, giving some wonderful performances, so I am very happy for her. She did it and is very proud of it. So am I. I was very impressed by her work.

She would be sitting there in the director’s armchair, looking at the monitor, saying, ‘Okay. Cut’. She was always on set, like I was. Stella is a very quick study, knows her onions, and has no worries.

N.H.: Talking about you and your wife, we shouldn’t forget about the third member of your family — your cat Niblo, meaning so much to you. I always see him lying in your lap while you’re playing the piano.

A.H.: We got Niblo in Budapest and brought him home. He’s ten now, and yes, I love him dearly. I’ve always had cats, ever since I was a boy. Of course, when they die, it brings a lot of grief, but I still love having them by my side. I think they are such beautiful creatures, and we can learn a lot from them.

As a matter of fact, I’m fascinated with all animals and have great respect for them. We should not underestimate their supreme intelligence — they just happen to be on a plain different from ours. As far as we know, they are not blessed, or rather not cursed with the knowledge of time and mortality. Having their own ways of coping with hardships and means of survival, they can actually teach us a lot of useful things. That’s why it really pains me to see some people treat animals disrespectfully. We help cats and dogs regularly and rescued one just recently. That young guy was pretty badly injured — I don’t know how — but now, he’s doing well.

N.H.: Unlike other characters, suffering from dementia, this one is presented from the inside. He’s completely lost his sense of identity and reality. When you work on such a role, do you need to learn about your character’s background and understand who he is since he himself doesn’t know it anymore?

A.H.: No, I just learn the lines.

N.H.: Did you do so, working on all your characters or specifically on this one?

A.H.: All of them. I mean, it’s a bit of a shallow answer, I guess, but I don’t see any point in belabouring it, diving deep, and getting intensely into it — I’ve been doing it for a long time, and this part was pretty straightforward for me to play. I don’t suffer from a memory loss yet. Having slowed down a lot, I don’t delve deeply into how to play a part. Florian Zeller named the char- acter Anthony, so it was easy for me to play him. I did add one line, though. When the doctor asked, ‘Date of birth?’, I automatically said, ‘31st December 1937’ — my actual birthday.

Having an obsessive brain, I do remember things like dates, days, and years. Fascinated by dates and time, I find it very important. Beyond that, with such a wonderful director and a great cast, playing my part was easy enough. The only problem was that my body started to ache. The only theory I have — maybe, a cockamamie one — is that if we take it too intensely, the brain follows suit, being not as sharp as we think it to be and having no sense of humour. So, if I am playing a man with dementia, thinking about getting old, my brain thinks about getting old too, and I have to let it know I am only playing a game. Nevertheless, my back aches, and so does the rest of my body. I suppose it was the four weeks of unconsciously getting into the part that caused it. Anyway, it was no big deal — just my thing. So, go and have some fun with it and enjoy it. It’s one of the greatest and most enjoyable things I’ve done.

I’ve been very fortunate working with people like Emma Thompson, Ian McKellen, Jim Carter, Olivia Colman, Olivia Williams, Mark Gatiss, Rufus Sewell, and Imogen Poots — wonderful actors indeed! So, it makes acting easy for me. When I am done, people ask me how I can enjoy it. Well, that’s my job. I mean, I enjoy working, getting out of the house, and doing something different. It’s always a novelty, but why make a big deal of it? I’ve been acting for a long time, having learnt to do my job, working with such great actors as Sir Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Peter O’Toole, Katherine Hepburn, and other people of suchlike calibre. I’ve been around the block a few times, watching them work. Never making a big deal of it, they just showed up on time, did their job, and went home. And there was some special grace about them all. I hoped I’d live long enough to be able to do the same — play with grace and respect for the script, the other actors, the crew, and everyone else involved, as they are the ones who make it all happen. If you just pay respect to what you do, it makes your life easier. And it doesn’t take a genius to do that.

A lot has been written about actors. As to me, I like watching American film stars — prime examples of great cinematic and stage acting — who made it look so good because they didn’t act so much. It’s people like Humphrey Bogart in ‘Casablanca’, Spencer Tracy, Bette Davis, and all those good old guys.

N.H.: The fascinating thing about this story is that growing old, each of us gets into a routine and likes to have things arranged in a certain way. Part of your character’s frustration is caused by somebody moving his things — that’s how he perceives it. How attentive to detail are you within your physical environment? How much of a stickler are you when it comes to keeping things in their proper places?

A.H.: You’d better ask my wife. Yeah, such words as ‘obsessive’ are so overloaded. Well, I am not obsessive. I like things to be in order but always make a mess anyway. I stack up books, and one day, they all fall down on me. You know, I call myself ‘a carnie’, which means ‘a carnival person’. I show up on the job, do it wherever we are in whatever exotic places, like Paris or Rome, and then move on to another project. It’s like being in the middle of a carnival. When a boy, I was fascinated by the circus and its chaotic lifestyle — not that my life is so chaotic, mind you. Well, I can’t really explain it — I think I’m pretty free while improvising. That’s why I never really plan anything.

N.H.: Is there a chair that must always be on a particular spot?

A.H.: The chair I consider mine, is usually occupied by my cat, so I don’t really know. Well, no, life is too short to worry about stupid things like that. I certainly don’t want to live in chaos. But no, I can’t take that seriously. I’m a bit of a ... No, not at all as I enjoy freedom.

Take my eating habits for example. I am rather careful about my ration because I’m getting older and don’t eat stuff likely to clog my arteries — hopefully. So, I have a fairly healthy diet. When it comes to food, wine, or anything like that, I am neither indifferent nor a gourmand — as long as it tastes fine, I couldn’t care less about the rest. So, I like oatmeal and a protein shake in the morning, maybe, a burger for lunch, and a veggie burger or something like that for dinner.

So, no, I don’t care much about stuff like that — such things don’t bother me, and I’m not obsessive in this respect. I don’t want to be fixed on anything, so things don’t have to be in the right place all the time. Let’s say I’m a bit of a mild chaos, as I don’t care to plan anything — I just go downstairs and play some Rachmaninoff and a bit of Brahms, without aiming at going to Carnegie Hall but for the sheer fun of it.

N.H.: ‘The Father’ reminded me of ‘King Lear’ — there are some things these films have in common. You’ve mentioned Emma Thompson, who played your character’s daughter. So did Olivia Colman. Having been ‘the father’ of such impressive ‘daughters’, could you compare working with these outstanding women and say a few words about the father-daughter relation- ship?

A.H.: Both Emma Thompson and Olivia Colman were quite extraordinary. ‘King Lear’ was my third work with Emma after ‘Howard’s End’ and‘The Remains Of The Day’ — in ‘Lear’, yes, she played my character’s daugh- ter. The most extraordinary thing about her is that she was quite ferocious and really powerful in her role, while on set, she was friendly and a lot of fun to deal with. The same was with Olivia Colman — a great actress too. Her emotional responses so spontaneous, I felt both amazed and bad in moments of my being particularly cruel to her.

Working with Emma Thompson, Olivia Colman, or whoever else as great as they are, is like playing tennis. I don’t play tennis or any other sports, actually, but I suppose that’s what it’s like — you have an opponent opposite you. In this case, it’s easy, and you don’t have to sweat or make a big deal of it.

We did that television adaptation of ‘King Lear’ in 2018 — almost five years ago now. I had played Lear 32 years before — in 1986 — a long time ago. It was a good production — David Hare’s splendid job. I was 49 at the time and technically alright. I tended to go over the top and was a bit all over the place, you know. Years later, Richard Eyre, the director of ‘The Dresser’, featuring Ian McKellen — another great actor I worked with — told me I ought to have another go at Lear. I said I’d like to but not in the theatre. He replied, ‘Okay. Let’s think about it’. In a year, I asked Richard Eyre if he thought we could do it. He answered affirmatively and cast it. We exchanged long emails, and I gave him my interpretation of what I felt the part was all about.

In essence, what I am saying is I’d lived another 32 years and gained a lot of life experience. The young cannot understand what it’s like to be a cantankerous old man, frightened of death, incapable of loving and afraid of being loved. Having made his ego so powerful, Lear torments in his macho way but just goes on toughening it up. And, of course, he has to pay an enormous price for that: isolation, loneliness, and, finally, madness.

As to my part in ‘The Father’, once, Anthony was obviously a successful man — a bright, disciplined, and well-ordered engineer, used to having his own way, probably, a bit of a tough father, not a bad person, but just an authoritarian. Finally, he starts ‘losing his anchors’ — a terrible thing for him, so he’s in panic. Then, having regained some lucidity, he starts flirting with a young woman — a most ridiculous thing to do. And in the end, just like King Lear, he has to say, ‘I feel I am losing all my leaves and branches in the wind, and I’ve got nowhere to rest my head’.

The most tragic thing about life is that we all have to face death. Alas, life is but terminal, so none of us can get off this planet alive. That’s the thing we have to face. My wonderful perspective of life is that while knowing not what’s round the corner, we might as well enjoy living. T.S. Eliot’s words explain it in the best way: ‘I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker, and I have seen the eternal footman hold my coat and snicker’.