A fortuitous conjunction of two solar-observing spacecraft may have unraveled a longstanding enigma of the sun. Information from NASA's Parker Solar Probe and the European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter indicates that plasma waves, known as Alfvén waves, might be energizing the solar wind as it exits the sun's outer atmosphere. This could explain why the solar wind is hotter and faster than heliophysicists anticipate, according to a study published on August 29 in Science.

These findings strongly suggest that Alfvén waves can heat and accelerate the solar wind, says Jean Perez, a plasma physicist at the Florida Institute of Technology in Melbourne, who was not part of the study. Since the beginning of the Space Age, scientists have been aware that the solar wind, a flow of charged particles emanating from the sun's atmosphere, accelerates as it spreads into the solar system. Theoretical calculations also predict that the solar wind's temperature should decrease as it expands into space, a decrease that does occur but at a slower rate than expected.

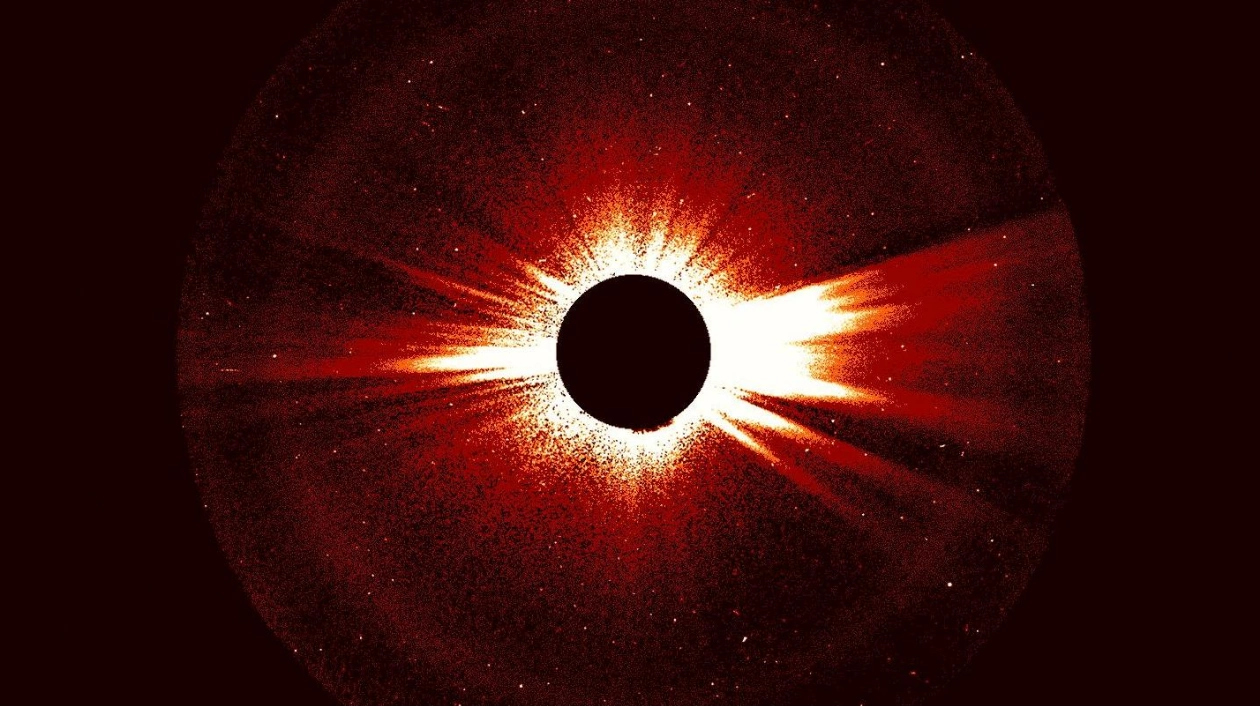

Previous observations from Earth have detected Alfvén waves near the sun, which are oscillations in the magnetic fields of the plasma coming from the sun. These waves, sometimes so large they create what are known as 'switchbacks', had the right amount of energy to explain the solar wind's speed and temperature, but direct evidence was missing until now. The Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter played crucial roles in this discovery.

In late February 2022, Parker was traversing a region about one-fifth the distance between the sun and Mercury, precisely where these switchbacking Alfvén waves occur. Coincidentally, Solar Orbiter passed through the same plasma stream a couple of days later near Venus. These two spacecraft intercepting the same solar wind allowed us to quantify the energy of these waves, says Yeimy Rivera, a heliophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass.

Parker recorded the plasma stream moving at about 1.4 million kilometers per hour, while Solar Orbiter measured it at 1.8 million km/h. The plasma at Solar Orbiter was also a scorching 200,000 degrees Celsius, three times hotter than theoretical predictions. The dissipation of Alfvén waves in the interim would have injected the right amount of energy into the solar wind to account for the increased speed and temperature measured by Solar Orbiter, according to Rivera and her team.

However, not all scientists are fully convinced that this mystery is solved. Some suggest that the team might not have fully accounted for the complexity of the solar wind, implying that the two probes might not have intercepted the same plasma stream. Rivera and Badman acknowledge the challenges in such measurements but believe they have done multiple checks to verify their observations, such as finding the same amount of helium in the streams the spacecraft passed through. They hope to further corroborate their findings by delving into the detailed physics behind the energy transfer between the Alfvén waves and the solar wind in the future.