The boy from Macksville, a small town nestled between Sydney and Brisbane, developed a unique habit. With every century he scored, he would collect the match ball, jotting down the date and score along the seam. These balls filled numerous baskets. His father, a banana farmer who set up the bowling machine, drove him around, and did everything love could ask, estimated that he had hit 68 or 70 hundreds before he left home at the age of 17. The runs, seemingly endless, transformed him into an almost mythical figure, a whisper that spread through towns and into the city. As a 12-year-old, he shared a player of the competition award with a 37-year-old.

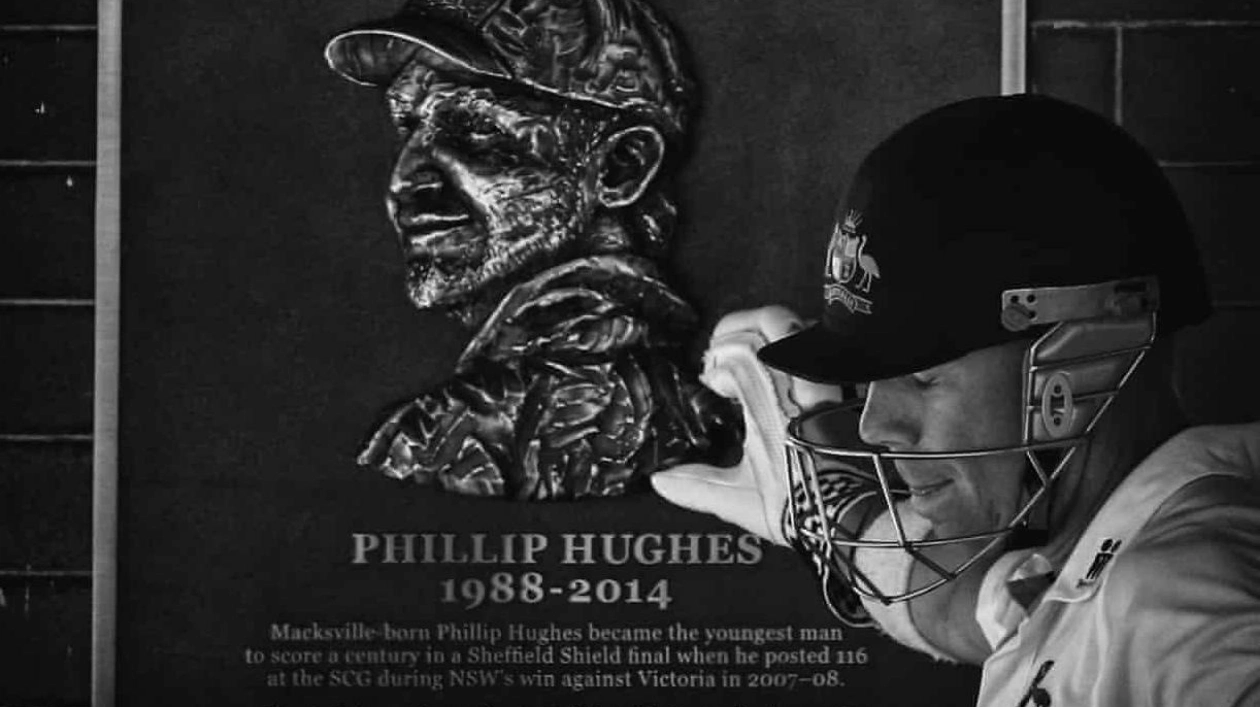

The biography of Phillip Hughes, penned affectionately by Australian journalists Malcolm Knox and Peter Lalor, is the source of these stories and more. I’ve spent the past week flipping through it, recalling what Hughes was: a prodigy. At 19, Hughes became the youngest to score a hundred in the final of the Sheffield Shield. At 20, he earned a Test cap. A few days later, he became the youngest to score two hundreds in a Test match, at Durban against a pace attack that needs no introduction: Steyn, Morkel, Ntini, and Kallis.

A few years later, Hughes became the first Australian to hit a century on his one-day international debut. A year and a half later, he became the first from the country to hit a List-A double-hundred. He did it in his own folksy style, with a technique that could ruffle the purists, a high backlift combined with a cut shot for the snappers, punctuated by a flourish of the hands.

Despite his obvious talent, when Hughes walked out to bat in a first-class match at the Sydney Cricket Ground 10 years ago this month, he found himself out of Australia’s red-ball side. He had been dropped several times, a victim of a more traditional style of selection. Time and a bit of trust would have unlocked an international batter not dissimilar to Travis Head, his younger teammate at South Australia. When batting at the SCG, he was pushing for another shot at Test cricket, with a series against India looming.

This is where the story tragically ends. Unbeaten on 63 against his former state team, New South Wales, a bouncer struck Hughes on the neck, resulting in his death two days later, just three days shy of his 26th birthday. It remains an unparalleled moment in cricket, a tragedy magnified by the innocence of the event. Hughes was batting, as he had done his whole life, playing the same game we all play: be it in the backyard, maidan, or village green. Those who did not know him grieved by posting pictures of their bats, left out for Hughes, one of those rare moments when social media offers genuine warmth.

Brendon McCullum’s New Zealand were in the middle of a Test against Pakistan in Sharjah when they learned of Hughes’s death. He told his tearful players that nothing they would do over the match would be judged, that there would be no consequences for failure. None of this really mattered after what had happened. They would end up scoring 690 at close to five an over, winning by an innings, changing the way McCullum approached the game.

Hughes’s funeral was broadcast and attended by revered names, including Virat Kohli and Brian Lara. Michael Clarke, his captain and close friend, spoke movingly about Hughes’s spirit: “I hope it never leaves.” Then, somehow, play resumed. Within days came a Test match at Adelaide where Mitchell Johnson, who had terrorized England a year earlier, felt sick after striking Kohli on the helmet. “Michael Clarke grabbed me and steered me back to my run-up, tried to get me to think about the next ball,” Johnson wrote in his autobiography. “He said it was just part of the game, get on with it. I think it was a difficult moment for him as well.”

Hughes remained at the forefront of minds when Australia were victorious, too, the players celebrating Nathan Lyon’s final wicket by sprinting to the 408 emblazoned on the outfield, their late teammate’s Test cap number. Has the game changed since? The question arises most Novembers. Helmet safety has evolved with the use of neck protectors and more attention has steadily been paid to the dangers of concussion, highlighted by the introduction of substitutes for the injury.

The bouncer and its place in the game has prompted some discussion. In 2021, the MCC began a “global consultation” to see whether the laws relating to the short ball needed adjustment, but the answer, revealed a year later, was for the status quo to remain. “The results of the consultation show that short-pitched bowling, within the Laws, is an important part of the makeup of the sport and in fact, to change it would materially change the game,” said Jamie Cox, the club’s then assistant secretary. But Hughes still comes to mind whenever someone’s helmet takes a blow. Those who were there at Lord’s in 2019, when Steve Smith fell to the floor after feeling the force of Jofra Archer, will remember the awful, brief hush that came with it, the fright that did not leave until Smith returned to his feet. That threat will never leave.

The tributes will be plentiful for Hughes in the next few days, recalling not just his talent but the universal love he garnered from teammates, the alternative view he offered when on the field. As Clarke recalled a decade ago: “Things were always put into perspective when Hughesy said: ‘Where else would you rather be, boys, than playing cricket for your country?’”

Source link: https://www.theguardian.com