It’s quite peculiar. In the city ahead of the Australia-India Test, Brisbane feels just as it always has: men strolling down Queen Street with boxes of mangoes, the Queensland humidity enveloping the city in its usual oppressive embrace as the air sluggishly moves along the river’s winding path. However, the Gabba Test doesn’t quite feel the same. For over three decades, this was the fortress where Australian teams remained invincible. The last visiting team to win here was the legendary West Indies squad of 1988, a feat achieved by the best of the best. But that era is over.

India broke the Gabba’s invincibility four years ago, chasing down a massive target thanks to Cheteshwar Pujara’s endurance and Rishabh Pant’s fearless approach. Two years later, South Africa’s Test ended in just two days, though they could have easily won on a pitch that proved unpredictable. Then, earlier this year, the modern West Indies, though weaker, had their moment of glory, with young Shamar Joseph dismantling the home team on a pitch that should have favored Australia. None of this guarantees that Australia won’t triumph in the next five days, or that the Test will even last that long. It simply highlights that the possibility of an upset is real, not just a hopeful fantasy. India will believe they can win if they can stabilize their batting. The challenge is immense, but so is the reward—a series lead heading into Melbourne and Sydney, venues that should suit them better than the previous three.

Another shift is the Gabba’s position in the Test schedule. In Australia, where tradition is born from repetition, Brisbane being the first Test of the season became an unshakable norm, even when it wasn’t. Visiting teams often faced defeat before they could even tell Vulture Street apart from Stanley. But Brisbane is rarely the first Test now, and won’t be for at least the next five years under Cricket Australia’s scheduling. This change, though it may unsettle some, brings genuine context to Gabba Tests. Previously, the only question was whether a touring team could escape with a draw due to rain or a flat pitch. Now, with the series tied at 1-1, there’s far more at stake.

A third change is that this Test returns to its pre-Christmas slot. Decades of winning teams often played in November or December. Australia’s two recent losses here came in January, after the summer heat had further worn down the pitch. Whether this timing makes a difference is uncertain, but it might. Those January Tests felt different even before the results confirmed it.

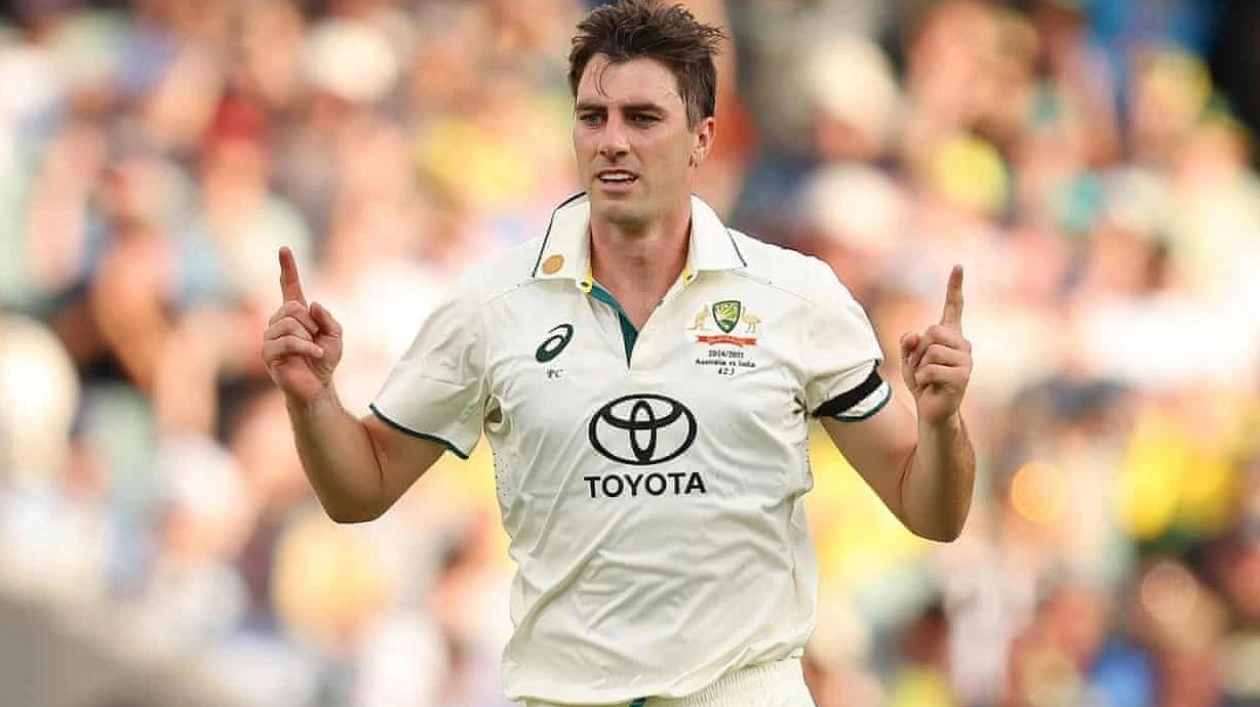

Josh Hazlewood is fit to play, boasting a strong Gabba record since his debut with 5 for 68 against India. Pat Cummins also performs better here than his overall career stats. A return to earlier scheduling might mean a return to historical norms, with Australia’s fast bowlers exploiting a batting lineup ill-suited to pace, bounce, and movement. That’s what’s expected on a pitch as green as an Irish cliché. But appearances can deceive; many visitors have learned that the pitch’s color can be cosmetic, masking a more straightforward reality. Many Gabba Tests have been won through patient batting rather than fast bowling.

If the pitch favors fast bowling, Australia has two concerns: a shaky batting lineup and facing Jasprit Bumrah. As India discovered against New Zealand on spinning tracks, home conditions with excessive venom can harm your own batting as much as the opposition’s. So much hinges on how that strip of grass behaves, and as history shows, no amount of record-studying can predict that.

Source link: https://www.theguardian.com