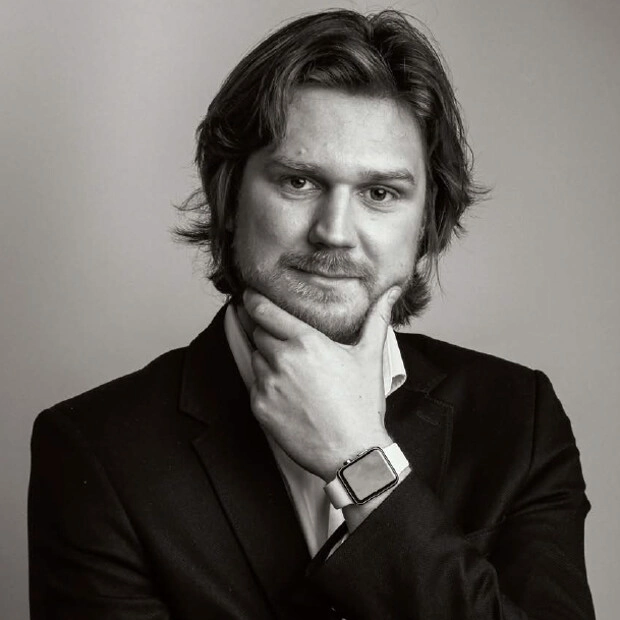

William Jones, an 18th century English writer and wanderer fascinated by the East, once composed a poem on the passion of Mars for the nurse Caïssa. As the story goes, the desire to seduce this unattainable beauty inspired the stern warrior to invent the game of chess. And although the poem is as far from classical mythology as it is from actual history, Caïssa quickly came to be considered the goddess-patroness of the game, a status she retains to this day. This is not surprising, as little in our civilisation can compare with chess in the intensity of the fervour and the dense concentration of temptations it inspires. A chess grandmaster since the age of twelve, Sergei Karjakin denies that Caïssa is for him a source of inspiration, though this has not hindered him in his pursuit of the chess crown.

My interest in chess was born when, while watching TV at the age of 5, I first heard the phrase, "As a pawn becomes a queen." It wasn’t from a show or a movie about chess, but in an advertisement for a bank. Yet these few words took hold of me, and I desperately wanted to understand what they meant — what is a pawn, or a queen? What does it mean for a pawn to become a queen? What kind of transformation is this? Then my dad told me about chess, and from that moment those words became an integral part of life.

I don’t much like inflated language. With all due respect, Caïssa is a fictional character; I draw my inspiration from my family. It might not be such a pretty story, but from my childhood onward, I was driven by the desire to win. I worked at it a lot. Between the ages of seven and eight, I was able to train for seven to eight hours a day, which is incredible for a child of that age. I did this on my own; no one forced me. By now, I have child of my own, am planning on another, and I know with certainty that it’s not possible to force a child to do something he doesn’t like for so long. At the age of twelve I became the youngest grandmaster in the world; it wasn’t a miracle, but the result of enormous, persistent effort, and not just mine alone. I want to tell all the young athletes out there that results don’t arise out of victory and inspiration, but from defeat, mistakes, and labour. You don’t enter a sport, and immediately beat everyone. It just doesn’t happen. I had many years of study and training, and only after all that did I see results. And even more important than sport and the desire to win, is that you have something you can rely on. For me it’s family. I always know that at home, they are waiting for me, that at home I’m loved — this inspires me to do great things.

Chess is first and foremost about self-control. In my training, I learned from childhood to control myself, and it’s not for nothing that they say my nervous system is one of the best in the game. In 2015, I participated in the World Cup, one of the largest chess tournaments. They use an elimination system, and five times during this tournament, I lost a game, and then I’d leave, as if I was done for. But then I’d come back, end up winning, and eventually I even won the Cup itself.

There are things that often distract chess players — someone coughing or talking in the hall, someone’s phone ringing — you can’t control everything.

There are things that often distract chess players — someone coughing or talking in the hall, someone’s phone ringing — you can’t control everything. If there isn’t a security system in place, and a phone hasn’t been silenced, it may ring. If a player doesn’t know how to tune out distractions, he loses focus, gets angry and nervous, and he’s much more likely to lose. I studied for a very long time to build up my concentration skills to such a point that it would be impossible to distract me. When I play, I’m not thinking about anything but chess. There is only the match — I’m thinking neither of victory and reward, nor of loss, nor of anything else in my life. Maybe that’s my secret; compared to others, I’m more concentrated.

It doesn’t matter where you live, but who you live with.

Outside of competition and training, I’ve got a lot going on, with various other people and projects. There are of course some material things, as we all live in the material world. I’m the official Ambassador of Mercedes; I’m passionate about cars. At the moment, the whole family is getting ready for something big — we’re moving to a new apartment in Moscow. We’re currently living in the suburbs. I wouldn’t say that this is unimportant to me, but it’s true that the feeling of happiness, of the fullness of life, depends on something quite different. As once said by a chess player, in words that have struck me as quite deep: "It doesn’t matter where you live, but who you live with." The main thing for me is who I’m around. Friends, acquaintances, and parents. I like to meet with my friends and relatives, to spend time with them.

When it comes to plans, my most ambitious is to return the chess crown to Russia. I nearly realised this in the last circuit, but Magnus Carlsen managed to hold on to the world title, keeping the crown in Norway.

I’m going to be involved in the popularisation of both chess and sport in general in our country, as a member of the Public Chamber of the Russian Federation, a new field for me. I’ll be speaking about how great it is to play chess, the board uniting people, giving everyone a chance to see the world in a new way. I hope it goes well. In any case, my match with Carlsen drew a lot of attention, which in recent years has been uncharacteristic of chess in our country. I am grateful to my fans and I hope that this interest will help elevate the level of the game. Children need to be taught how to play as early as possible, ideally starting from preschool age! But even for school kids, it’s an excellent activity. Chess helps with concentration, and it teaches responsibility, because once you’ve made a move, you can’t fix it. This helps later in life with thinking before you act.

I am optimistic, because these days, they’re making films about chess, and I see a definite breakthrough in this; it’s new. Recently there was a movie about Bobby Fischer — I was at the premiere, and I really liked it. There was a film about Marcus Carlsen, and now there’s a film about me in its final stages.

My own history is proof that it’s possible to discover chess as your calling through a chance encoun- ter with a quip about a pawn and a queen, heard on TV. So it’s really important that children, as often as pos- sible, encounter stories about chess, so that their interest can awaken at the earliest age. And it’s important for there to be people who can an- swer their questions. I don’t know what could be better than chess at instilling the idea of growth, of progressing from a pawn into a queen. It’s quite obvious to me that at the age of five, I felt like a small brave pawn beginning my journey — now I can call myself a queen, ready to fight for the chess crown.