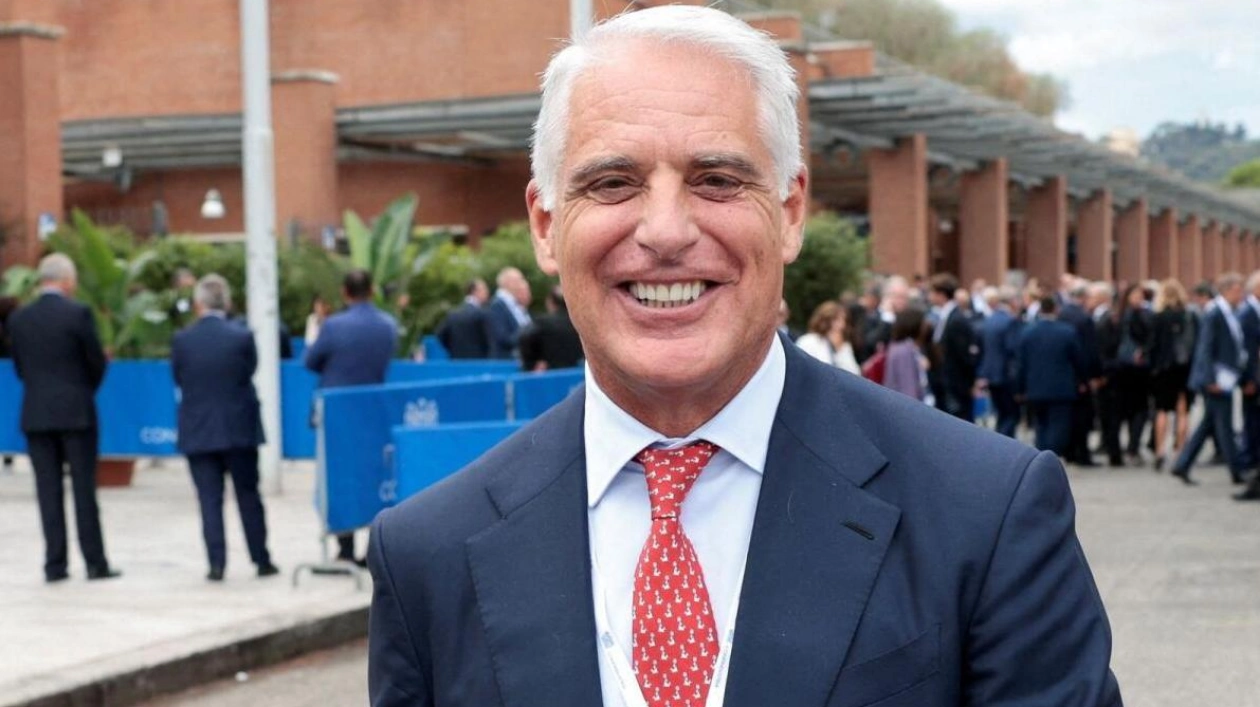

For decades, Andrea Orcel has been the ‘rainmaker’ whom CEOs sought for counsel on major transactions that reshaped the banking sector. Now, as the chief executive of UniCredit, the Italian is facing his most significant challenge yet—breaking through Europe’s entrenched political resistance to cross-border mergers. Orcel recently signaled his merger ambitions when his Italian bank acquired a significant stake in Commerzbank, becoming its second-largest shareholder after the German government, which holds a stake following a crisis-era rescue. UniCredit’s move, codenamed ‘Flash’ after Orcel’s dog, has sparked a frantic search for direction in Berlin, opposition from labor unions, and a defensive strategy from Germany’s second-largest listed lender. Orcel now aims to initiate discussions on a combination that he believes would “create a much stronger competitor” in Germany. This strategic move comes after years of calls for Europe to enhance its banks’ competitiveness against larger US and Asian rivals.

Orcel faces substantial obstacles. Cross-border European banking deals have been hindered by factors including years of meager profitability that have left lenders too weak to pursue such ventures. Additionally, regulatory barriers to the free movement of resources across borders have been reinforced by political preferences for home-grown ‘champions’. A turnaround at UniCredit has overcome one of these hurdles. Unlike its peers, UniCredit has the financial strength for a bold combination after reaping substantial profits. However, navigating national politics will be the tougher challenge.

“Most European countries have overpriced banking services because they are controlled by a handful of local banks,” noted Karel Lannoo of the Centre for European Policy Studies. “The German reaction to UniCredit’s interest in Commerzbank demonstrates the resistance to changing this,” Lannoo added. “It’s the Italians coming to teach the Germans a lesson in the free market, and the Germans don’t appreciate it.” Some in Germany’s government have been irritated by what they perceived as a stealth move by UniCredit, which built up its 9% stake overnight, according to a source who spoke to Reuters. UniCredit stated that it had been transparent with its actions, which come at a sensitive time in Germany, with its coalition government, one of the least popular in recent history, gearing up for national elections next year. Recent gains for the far-right and far-left are pressuring the three-party coalition, particularly the smallest member, the liberal FDP party, which oversees the finance ministry. Meanwhile, sources close to the matter say that Rome views Milan-based UniCredit’s efforts to build a large European bank favorably as long as it maintains its central functions in Italy. However, Italy is maintaining a cautious distance, and there are no indications of support for UniCredit’s venture.

A UniCredit-Commerzbank merger would be the largest cross-border European banking deal since the global financial crisis. Orcel is betting that UniCredit’s existing ties in Germany—it already owns German lender HVB—and its ambition for a combined group will sway politicians. “Europe needs banks capable of supporting every industry and the development of Europe so that we can be an economic bloc that can stand up to the US and China,” Orcel told Bloomberg last week. This echoes a long-standing message from officials in Brussels, Europe’s political hub. Last week, in a comprehensive report on how to make Europe more competitive, former European Central Bank president Mario Draghi urged the EU to address the obstacles to cross-border banking. Orcel, who walked away from an initial agreement to buy troubled Monte dei Paschi in 2021, disrupting then Italian Prime Minister Draghi’s efforts to resolve the bank’s long-standing issues, can be unyielding. UniCredit has sued its chief supervisor, the ECB, which has ordered it to retreat in Russia. In the face of considerable resistance in Germany, Orcel ruled out a hostile bid on Thursday, adopting a more conciliatory approach. If successful, a deal could reshape thinking elsewhere in Europe.

“Imagine if someone today were to make a bid for the government stake in Monte Dei Paschi; they would never manage to pull it off,” said Algebris Chief Investment Officer Sebastiano Pirro. “If (France’s) BNP were to bid, it would be simply impossible. They have a preference for that to remain domestically. But if UniCredit were to buy a German bank, then all options are on the table,” said Pirro, whose hedge fund is an investor in UniCredit and Commerzbank and supports a tie-up. Orcel’s next challenge is securing ECB approval to acquire up to 30% of Commerzbank. Analysts believe it is unlikely to obstruct the move, given years of calls for such deals. “The European single market in financial services is a work in progress, but mergers like UniCredit and Commerzbank would help turn it into a reality,” said Nicolas Veron of Brussels think tank Bruegel. Some question whether Orcel should even attempt such a deal. M&A “needs to be complementary; it needs to be voluntary, and often, very often, it needs to be in the same country,” said Patrick Lemmens, fund manager at Robeco, who owns shares in UniCredit. “The moment you go across borders and there’s little overlap, it becomes just more difficult.”