The banner in Legia Warsaw’s near-empty away section spoke volumes, conveying more than any football match ever could. Below, Dinamo Minsk were suffering a 4-0 defeat against the home side in last week’s Conference League fixture, but no one seemed to mind. “Voices silenced but must not be forgotten,” it read, with an image of Belarus transformed to show hands reaching through prison bars. “Free all political prisoners.” After the match, attempts by exiled Belarusian media to engage Dinamo’s players in non-football discussions were met with silence. The risks were too high, the potential for retribution too great; everyone understood that. Back across the border they went: another hollow representation of a sporting institution, serving only the government of a pariah state.

Four Dinamo players are now preparing for national team duty this week. On Friday evening, they will face Northern Ireland at Windsor Park in a Nations League fixture that was once uncertain. Belarus has been banned from hosting matches in their home country since March 2022, a sanction imposed by Fifa and Uefa due to their role in facilitating the illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine. Entry into other countries is at the host’s discretion, and the UK government, which has imposed sanctions on Belarus for the same reason, took time to decide whether to grant the footballers visas. Permission was finally granted two weeks ago, much to the relief of the Irish FA, which feared they would suffer if the fixture were moved abroad. So, Belarus will play in Belfast, hoping to replicate last month’s “home” draw in Zalaegerszeg, Hungary, and, consciously or not, trying to deflect from the notion that their presence taints the sport.

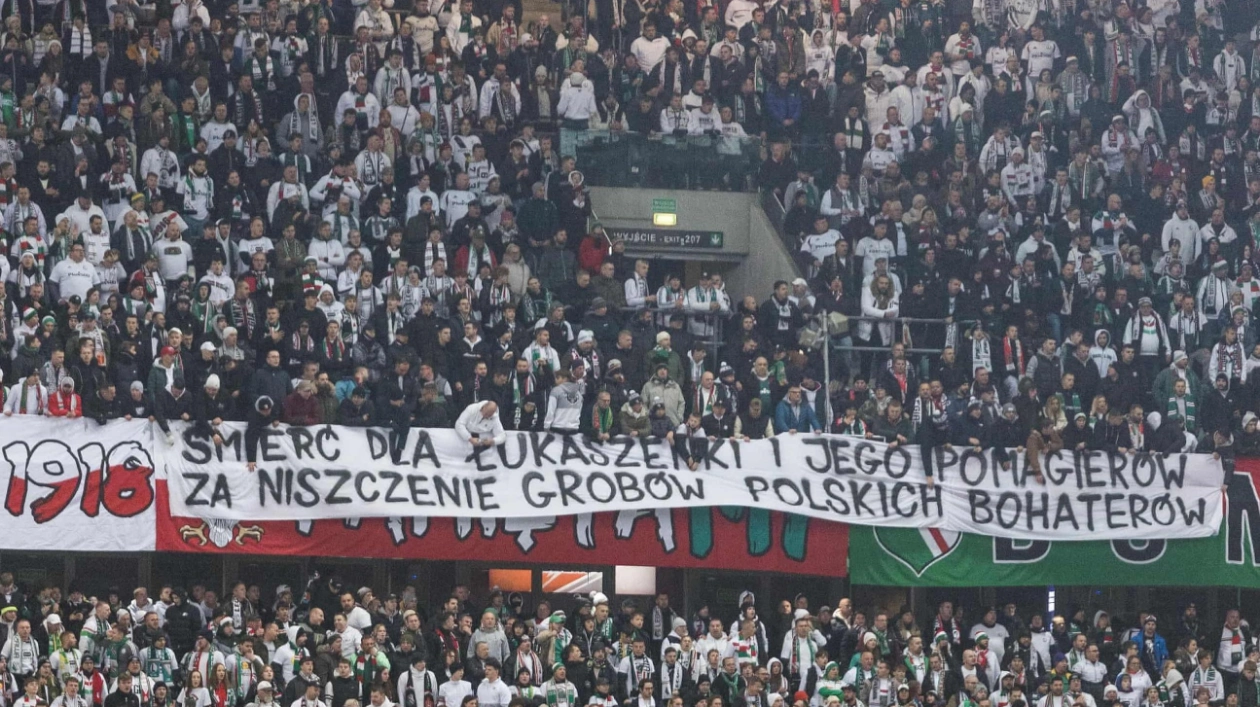

Allowing Belarus to participate on the international stage tacitly endorses the manifold horrors they are complicit in. Their involvement with Russia’s abuses is appalling enough, but when their atrocious human rights record, which includes persecuting footballers, is considered, the situation becomes even more dire. There are believed to be over 1,300 political prisoners in Belarus, the same individuals referenced by those fans in Warsaw. These incarcerations often result from the slightest opposition to Alexander Lukashenko’s authoritarian regime. More than one player has spent time in jail. About 48 footballers are believed to have been blacklisted by the Belarusian Ministry of Sport for expressing anti-government views, participating in demonstrations, or refusing to show support. This has led to some players having their contracts refused or terminated, effectively meaning the national team is filled only with players deemed compatible with the state.

While the local football federation has managed to rehabilitate some of the blacklisted players’ domestic careers over the past year, attempts to extend this to those with national team potential have reportedly been blocked at the government level. None of international football’s governing bodies seem overly concerned about state interference in one of their member associations. The fear in Belarus is that, with Lukashenko’s likely re-election in late January, the atmosphere of repression will worsen. Yet, football continues, and on Monday, the national team coach, Carlos Alos, was given a two-year contract extension, reportedly including a pay rise. Alos, a 49-year-old Spaniard, has been in charge for just over a year and has previously worked in Rwanda and Qatar. On a sporting level, Alos has achieved some success, leading a struggling team to impressive early draws against Switzerland and Romania, along with a victory in Kosovo. They are unbeaten in four games and are just a point behind Northern Ireland, who lead group three of Nations League C. “We still have a chance for first place,” Alos said. “We cannot train without thinking about victory. We are setting maximum goals for the match.”

Among Alos’s tasks is to qualify Belarus for the 2026 World Cup, an outcome that seems highly unlikely. A more pressing question is how football’s governing bodies will view them by then. Their presence on the continental scene, whether at national team or club level, is hardly popular. One practical example is Dinamo’s arrangement to host this season’s “home” Conference League games in friendly Azerbaijan, which is frustrating for opposing clubs forced into lengthy trips to closed-door ties with no financial reward. However, they and Russia have many advocates within Uefa and Fifa. Some in the game worry that, if relations with the two countries become normalized under Donald Trump’s US presidency, pressure will grow to swiftly ease sporting sanctions. Dinamo had chosen not to organize tickets for their fans to attend the Legia game, despite the countries’ proximity and the club’s profile within Belarus. Perhaps they knew what was coming. The banner highlighting the prisoners’ plight was far from the only show of anger with Lukashenko’s regime to make its way into the stadium. Sections of the Legia support visibly and audibly lent their weight too. It remains to be seen whether Windsor Park will see similar displays; regardless, Northern Ireland’s visitors are merely a puppet for a country that has no sporting credibility left.

Source link: https://www.theguardian.com