NASA’s Europa Clipper spacecraft is set to embark on a mission that could unravel a 25-year-old enigma: Is there life in the ocean hidden beneath the icy shell of Jupiter’s moon Europa? “This mission has been a dream for 25 years, ever since I was in graduate school,” says planetary geologist Cynthia Phillips of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “It’s a generational mission.” Originally scheduled for an October 10 launch from Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the mission was postponed due to Hurricane Milton, but is now expected to launch later this month or in early November.

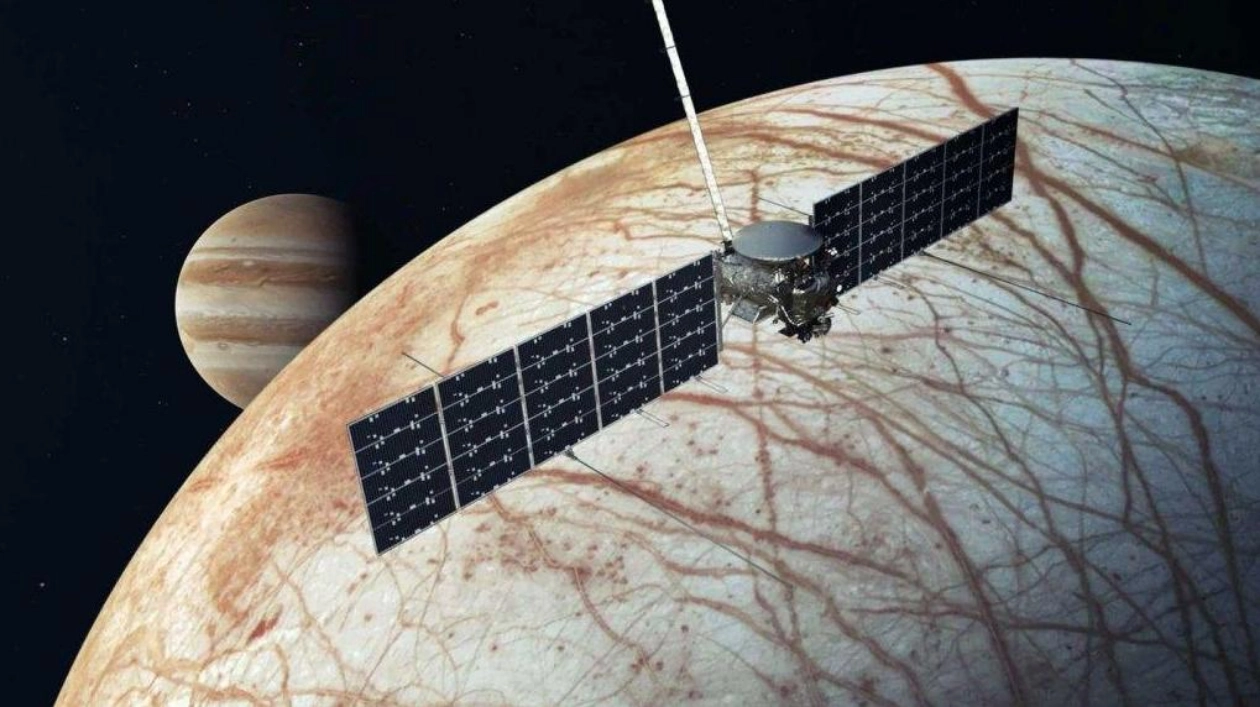

After a five-and-a-half-year journey to Jupiter, Clipper will enter orbit around the giant planet in April 2030, conducting repeated flybys of Europa to capture images of its icy surface, measure its chemical composition, and deduce its internal structure. “We believe that ocean worlds could be common beyond our solar system,” said NASA’s head of planetary science Gina DiBraccio in a September 17 news conference. “Clipper will be the first comprehensive mission to assess habitability on what might be the most common type of habitable world in the universe.”

Planetary scientists have been increasingly confident that Europa harbors a subsurface ocean since NASA’s Galileo spacecraft visited Jupiter in the 1990s. “During the Galileo mission, it was like a detective story,” Phillips says. The clues accumulated: a lack of craters indicating a constantly changing surface, stripes and cracks suggesting upwelling from below, and “chaos terrain” resembling tilted icebergs in a sloshy sea. The final piece was the detection of an internal magnetic field induced by Jupiter’s external one, which Phillips calls “the coup de grâce.” The only plausible geological material capable of carrying this magnetic field is saltwater.

On Earth, water signifies life, but the findings on Europa were not enough to declare it habitable. Many questions remain: How deep is the ocean? How thick is the ice shell? And how do they interact? Could material from the surface reach the ocean to nourish potential microbes? Europa Clipper, named after the fast clipper ships of the 19th century, is poised to continue where Galileo left off. The spacecraft will investigate Europa’s habitability by searching for three key ingredients: water, energy, and organic compounds.

Clipper won’t orbit Europa directly due to Jupiter’s harsh radiation environment, which could damage spacecraft components. Instead, it will repeatedly dip in and out of the radiation zone to fly past Europa at least 49 times, aiming all nine of its instruments at the moon each time, before retreating to safer territory to process data and send it back to Earth. One of Clipper’s first tasks will be to confirm or refute the presence of the subsurface ocean by measuring the moon’s gravitational pull on the spacecraft, revealing details about its interior. Next, Clipper will take high-resolution images and spectra, providing insights into the surface’s chemical composition that Galileo could not.

Clipper will also explore the thickness of the crust, the depth of the ocean, and their interactions. However, it won’t reach the ocean floor, where rock and water meet, potentially the most likely place for microbial ecosystems, similar to Earth’s seafloor vents. But there is strong circumstantial evidence that water occasionally reaches the surface, either in plumes of vapor or slower seeping streams or lakes, depositing any carried material onto the ice. Clipper will search for chemicals on the surface and infer what might be present in the depths.

“The holy grail would be finding something like an amino acid on the surface,” says Bonnie Buratti, deputy project scientist at JPL. “But even detecting a lot of organic molecules would be strong evidence that we have all the requisites for life.” Clipper won’t directly search for life. “We don’t have a tricorder to point at Europa and say, ‘It’s life, Jim!’” Phillips says. “It will be multiple lines of indirect evidence.”

Phillips, who has waited so long for this mission, doesn’t expect to see a follow-up mission in her lifetime. “I hope the momentum will build,” she says. “I accept that I probably won’t see that Europa submarine, but hopefully my kids or maybe my grandkids will.”