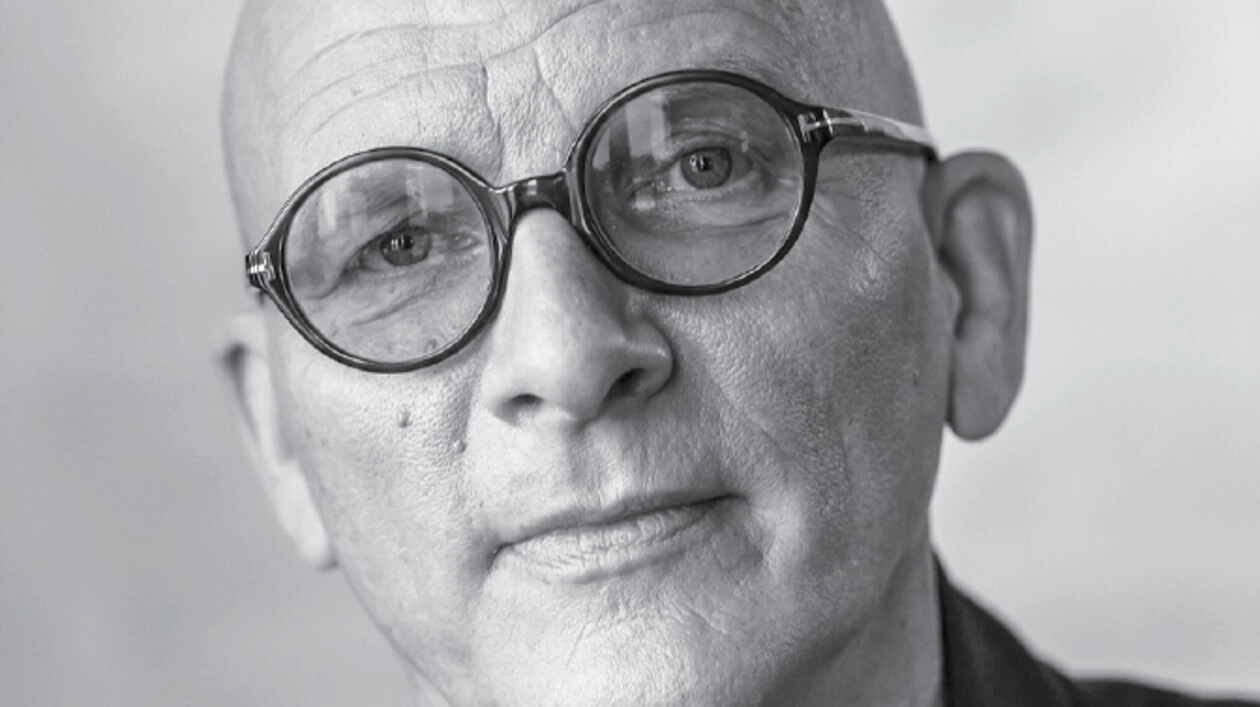

Stanisław Jerzy Lec once snickered: "The electronic brain is going to think for us in the same way the electric chair dies for us." But many people now don't find this so apparent. People have developed computer technology to such an extent that we've come to see it as a real threat; it’s almost as if technological creations will soon enough be capable of taking the remote controls away from their creators. At the end of the last century, Funky Business, the worldwide bestseller, managed to predict much of what we see happening today. The book’s author, Swedish economist Kjell Nordström, presents his column on how machine will never become master, and on the necessity of its development for humankind.

Evolution can be neither right nor wrong, it simply is the way it is. There’s no point in missing the past, because it’ll never return, and the future can’t be predicted it needs to be created. But something that can be confirmed is that we must continue on along a single road with artificial intelligence.

I don’t believe it’ll lead to the defeat of man. It’s all about how we relate to machines. We must understand that the main thing that unites us to them is our ability to make mistakes. A person’s prerogative is that, unlike a machine, we can fumble: we can make bad decisions, fall in love with the wrong person… Machines don’t do that. They don’t get to acquire a sense of humour, because the laughter of people around us tends to trigger us to do something incorrectly this is just one type of "error." It’s a territory that will always be a part of the human sphere. It’s a territory that artificial intelligence will never step foot on, perhaps for one simple reason: people don’t need machines that make mistakes.

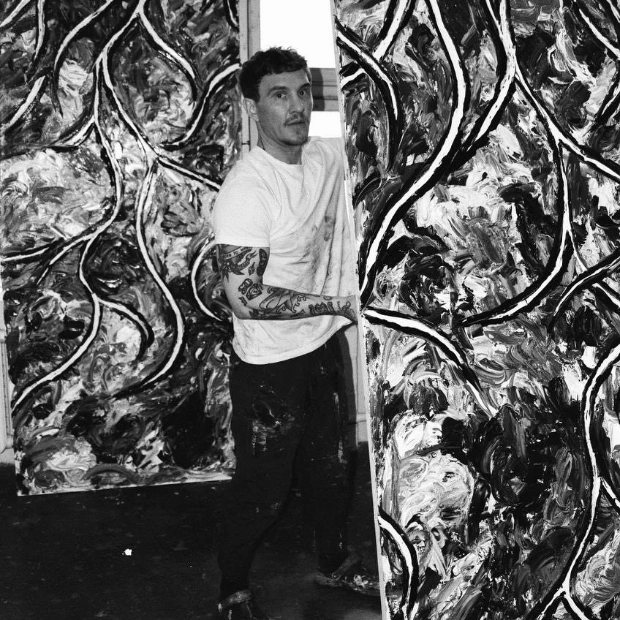

If it is a human privilege to err, then it also means that we can be creators, because it’s impossible to create without making mistakes. Creation requires experimentation you must always be thinking, trying, observ-ing what happened. And it's such a human thing, to be inventive, and conduct experiments, and make adjustments accordingly. I'm not talking about small, technical adjustments, which, yes, are made by machines that are programmed to edit already existing mechanisms. It is only humans who are in the position to turn things up-side down: to come up with something new. And that’s because they, at very least, have a vision, a fantasy.

This is a significant difference between humans and developed primates like chimpanzees or orangutans the presence of the imagination. We can experience things that don’t physically exist. Take God, for example. How could you go about explaining to a chimpanzee that up there, overhead, there’s someone watching our lives? It would be impossible to convince a chimpanzee that something might happen to him after death. Religion is a fantasy of the people, a "history" they invented. And there are also modern "stories," which, I think, pose much more serious problems than they may seem to. One of them is the "history" of the national state. That Italy is here, and Austria there, and Ukraine, over there, and so on. The boundaries that we have built only cause more problems. Many of them are completely artificial in the sense that yes, they exist, but that there are people of the same nationality on different sides of the borders. Kurds, for example, who live in Russia and Ukraine, and also in Iraq and Iran. If you were to ask me what I would change, it would be to remove the borders. Without them, people could be much better united.

We ask computers about simple things, like playing chess or driving a car. But issues like how to resolve the conflict in the Middle East aren’t so simple. There’s no program for things like that. So how do Palestine and Israel come to a reconciliation? That’s a difficult problem. How do we help Muslims become happier, so that they don’t crash into crowds of people in New York? A computer can’t provide much help here. There’s still plenty left for human beings to work on, believe me.

But people are still afraid of technology. "What’s next?! Are we going to be left without jobs?" A lot of people are concerned about that. But let’s the example of the modern doctor. Whether we’re talking about a Russian, Swiss, or American one, it doesn’t matter. The fact is, today, the doctor is essentially a secretary who gets paid a high salary, because he’s forced to fill out all kinds of paperwork, essentially doing secretarial work. Administrative duties take up more than half of his working time. But this is exactly the kind of job that we could be giving to our wonderful machines! And if we gave that work to the machines, your doctor would have more time to find out that you had spent a few months in India, and then to find out what you ate there, and finally understand what's really going on with your digestive system.

These days, machines have been introduced into practically every sphere of professional activi-ty. But the only thing that happens as a consequence of this is that we, human beings, have more time for human activities. Some accounting firms KPMJ, Ernst & Young are incorporating machines and are still hiring more people than ever. They’re hiring more, not less. We can see how machines and people cooperate. When I want to go to Stockholm, for example, I use the Internet that is, machine intelligence to ask my friends which hotel is the best, which places in this city I should visit. It’s the same case in any other sphere. I think people don’t quite compre-hend that artificial intelligence will never be able to perform absolutely all of the work for us. Machines will continue to do those things that it can do well. Everything that can be digitised, people will digitise. But there will always be some areas in which it can’t equal you or me. That’s how it always will be, until the end of our days.

Yes, many industries are now using machines or what are known as machine learning algorithms. From finance, to entertainment, to a number of other fields. But, when everyone is using the same algorithms, those algo-rithms need to be changed. Otherwise, you’re running the risk of losing the competition. It’s essential to be unique. This was made very clear to me one day, during a lecture by Yale University Professor Harold Bloom.

The green Stockholm summer was shining just outside the window of the auditorium, and yet only Bloom, his literature lecture so beautiful in itself, managed to attract the attention of the listeners. Just when it had seemed to us that he had finished speaking, the professor turned around, looked at us piercingly, and declared, "Remember, ladies and gentlemen! There are only twenty-six books you should read all the rest are just copies." Then he launched into a list of the books. Dostoevsky made the cut. So did Shakespeare, and Kafka. What exactly had Bloom meant? I'm not sure, but he seems to have been arguing that there are twenty-six original works about people and the problems connected with them. One of those problems is love. And then there are books about power and strength. Twenty-six stories. The rest are just copies. Or, as I’ve come to call them, "karaoke." We’re trying to transcribe what has already been created by others.

In the evening, I walked along the Swedish capital and decided to take a closer look at the city. I passed by the Radisson hotel; it was no different at all from any other hotel. A reception desk, hotel rooms. I glanced up and down the street at the cars flying by. They, too, were all alike. I couldn’t make out what had just passed me. Was it an Opel, or a Toyota? Or could it have been a Volkswagen? We can make endless copies of anything, but doing so isn’t really creating. And the most terrifying thing is that this is a challenge that faces us not only in literature. So how is it, then, that we regain our originality?