Lara Palmer: What is your life philosophy?

Lorenzo Quinn: Memento mori.

L.P.: Could you explain it in more detail?

L.Q.: Life is short, so it must be lived now. I try to follow this simple philosophy to the best of my ability though, at times, it’s easier said than done. Especially, when you have to take so many things into consideration and make an important decision, entailing inevitable consequences. Still, difficult as it is, decisions have to be made not to waste the wonderful time of your life.

SUPPORT Venice, Italy Installed in 2017

SUPPORT Venice, Italy Installed in 2017L.P.: Exactly! How would you describe your artistic mission?

L.Q.: To spread unity and love worldwide. That’s what I’ve always wanted with all my heart. And that’s what I keep on doing. My art is all about communicating messages and bringing all of us together.

L.P.: What is the main theme of your works?

L.Q.: It’s all about things that can unite people, like love, the passage of time, and death. Also social matters. Sustainability. And the need to protect nature. All these things are of paramount importance, so I talk about them in a lot of my works. Touching upon many subjects, I try to do everything in a thousand positive ways. As I’ve just said, I’m always looking to what unites rather than separates humanity. It’s not at all easy as, unfortunately, there’s so much powerful negativism on the media landscape. So, we need to send a lot of yet more powerful positive messages to overcome it. Thus, it’s a constant struggle.

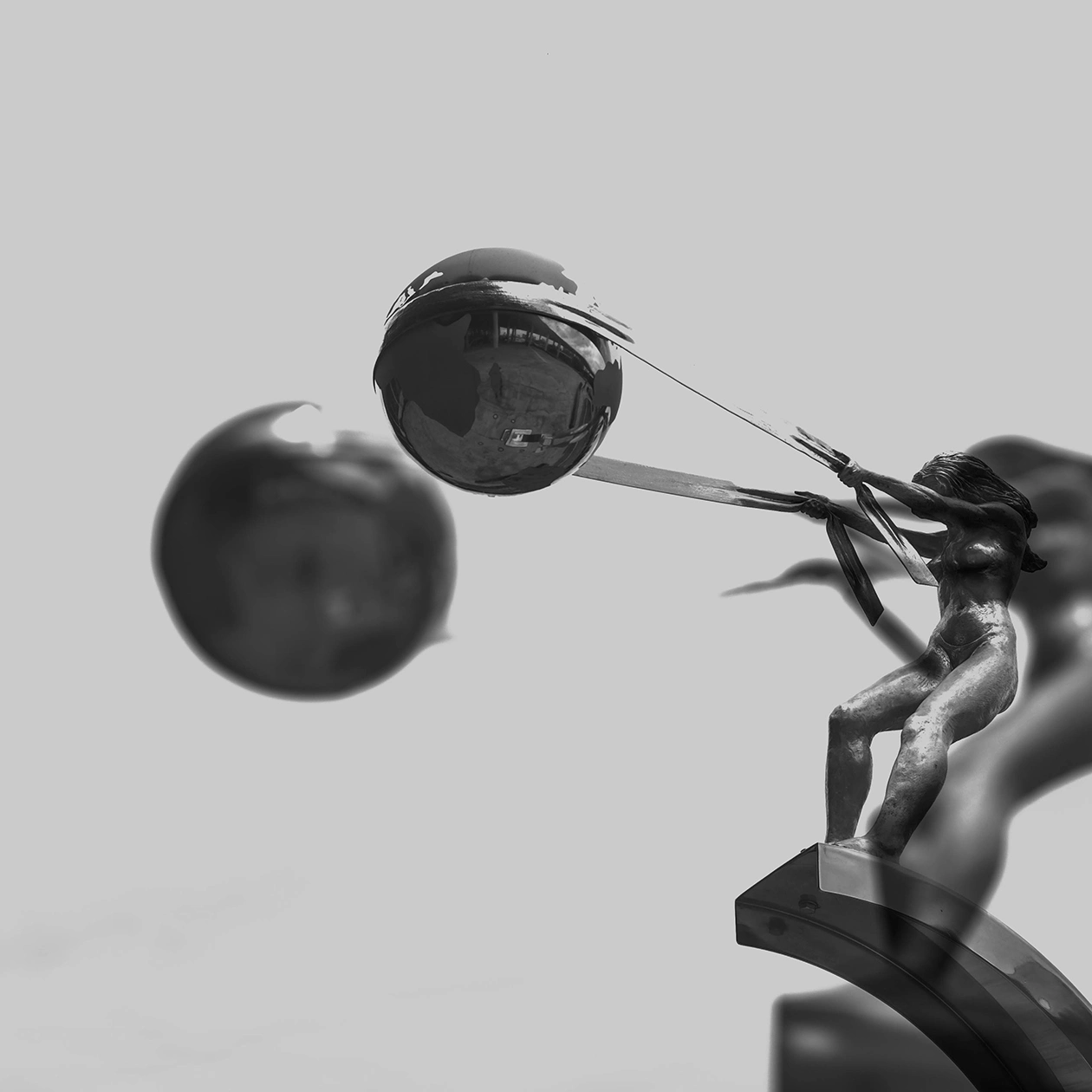

LEAP OF FAITH Knightsbridge, London

LEAP OF FAITH Knightsbridge, LondonL.P.: According to one of your interviews, your work is all about the balance between the dark and bright sides of human nature. Could you dwell on this point a little bit?

L.Q.: Yes, indeed, we are constantly forced to make decisions and face inevitable choices, their results making up our personalities. An empathetic person makes empathetic decisions. I basically try to encourage people to make as many good and positive decisions as possible. And my mission is just to keep on doing just that.

L.P.: Speaking about making important decisions, I’d like to ask you about something else. Having started with painting, how did you finally decide to become a sculptor?

L.Q.: Well, my starting painting was not something that I actually decided. It was something that I, kind of, fell into or rather fell in love head over heels with you know. So, for me it was such a personal matter – working on a canvas for six months or even a year, putting so much of myself into it and then having to sell it. No wonder, I felt really bad about selling my works. The money I got would be gone, alas, all too soon while the buyers would get a chance to enjoy my paintings for the rest of their lives. In my view, it was an unfair transaction. With sculptures, it’s different because each has a mould that remains with me when the job’s done. The client takes away my sculpture, but I can always make another one for myself. Besides, it’s usually a series, so I still stay in touch with my previous works. Thus, sculpture is more about sharing rather than losing my works for good, which is more like it for me.

The Force of Nature, White Bronze

The Force of Nature, White BronzeL.P.: What was most exciting on your way to success and fame? Have you got a story to share?

L.Q.: I’ve been working for 36 years, so I’ve got numerable stories. I can- not share one, as there’s no such a thing as ‘one’ story to share. I can think only of one capitalising all the others. People often ask me to name my most successful piece. A few female ones, I guess, could be mentioned. While in terms of popularity, it’s probably the one I did in Venice - the hands coming out of the water, called ‘Support’. I was very lucky to enjoy a lot of success there. Then, I guess the piece I did in front of the Pyramids. It had taken me more than 30 years of hard work to get to that point. And it’s not like movies or music as some might think. You sing a song that becomes a hit or play a successful role in a movie, but before long, you discover that nobody remembers you. Many have been a one-time success to never come up with another hit. Must be very frustrating. I think sculpturing is a very different kind of career, in which one single event cannot mark a success. It’s a long series of little events, eventually leading you to a big one.

L.P.: Why did you choose to specialise in the human figure?

L.Q.: I chose figures because they speak volumes about humans. My work is all about us and our relationships. Any observer can understand this kind of sculpture easily enough. An abstract message in an abstract form might not be universally understood as I want, so I have to speak a universal language. I make hands a lot because they denote universally understandable gestures. That’s what I find to be of utmost importance.

VROOM VROOM Park Lane, London Installed in 2011

VROOM VROOM Park Lane, London Installed in 2011L.P.: You say your way of working is similar to writing a book. Could you talk a little bit about how your artistic process starts?

L.Q.: First, I need to know what the sculpture’s story is going to be about, and what message I want to convey. So, I create a working title, inspiring enough, helping me to figure out the idea of the new sculpture. The working title is, indeed, extremely important. Then, I choose a few words and make up a few sentences, leading me to finding the idea of the sculpture. Having done that, I have to think of a story. If it is, say, Alexander-the-Great, I need to understand what his story is going to be about – his first steps to glory, the end of his life, or a battle he is famous for. That’s how a writer plans his new book. Same with my artwork. Say, I want to make a sculpture, showing a male-female relationship. OK. There should be two figures. First, I ask myself several questions: What will be the sculpture about? What will be its message, good or bad? What part or period of their lives will it be about? Have they just met or separated? And so on. That’s how I start working. So, basically, a sculpture always starts with a message I want to transmit. Then, I draw the idea of the sculpture. Only then, comes the last but not least part - the aesthetics.

DOLCE VITA, ENGLAND Hyde Park, Park Lane, London, England Installed in October 2012

DOLCE VITA, ENGLAND Hyde Park, Park Lane, London, England Installed in October 2012L.P.: Are there any sculptors or artists you could call your favourites? If so, could you name some?

L.Q.: I love all the Renaissance artists. By all means, Michelangelo – a never-ending source of my inspiration. And, of course, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Gian-Lorenzo Bernini, and Roden, to name just a few. As to modern artists, I can’t say I’m inspired by any, but I do like a few, such as Jorge Marin, a Mexican sculptor and painter, or Jaume Plensa, a Spanish visual artist and sculptor, to name a couple. But as to inspiration, nothing can beat the classic Renaissance art.

L.P.: Which three features of your character define you the best?

L.Q.: Three main features of mine? Well, for sure, willpower. Then, stubbornness. And, I guess, impulsiveness. Maybe, these features are not the best, but they do define me best of all. That is who I am.

L.P.: Is there anything you have been fighting with throughout your whole life?

L.Q.: Yeah, my impulsiveness.

L.P.: I see. What do you dislike in people the most?

L.Q.: What do I dislike in people? Well, dishonesty, of course. I guess, outright lying. Then, lack of empathy. Also apathy. And violence.

GIVE Rosewood Hotel, London, United Kingdom Installed in October 2022

GIVE Rosewood Hotel, London, United Kingdom Installed in October 2022L.P.: You’re an Italian American, currently living in Spain. Your works are exhibited all over the world - in America, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. I know you want your art to be universal. So, creating a global art form must be most important for you, right?

L.Q.: Right. I do want my work to be universally acclaimed. It’s amazing to see my art placed in the public limelight, with a fabulous environment and the whole nine yards. It’s not the reason why I do what I do though, but when it happens, it is something fantastic indeed.

L.P.: Why do people pay so much attention to those giant hands, emerging from a Venetian canal? Why do you think this piece of your art has been received so well? Do you agree it was this very masterpiece that made you so famous?

L.Q.: Indeed, it has been considered an iconic art piece of mine for quite some time. Well, I guess I was just lucky. It was all about where it was presented actually. That’s why people loved it so much. It’s a complex idea, rendered in a very simple way that everybody can understand. At the end of the day, the simpler, the better, as it is more universal. In the meantime, transforming a complex idea into a simple form is anything but easy. So, the ability to convey complex issues in a simple way is one of my main artistic qualities. That’s what I’ve been doing for all these years.

GIVE Rosewood Hotel, London, United Kingdom Installed in October 2022

GIVE Rosewood Hotel, London, United Kingdom Installed in October 2022L.P.: What’s the best way to understand contemporary art and transcend its boundaries?

L.Q.: You know there’s no ‘best way to understand’ contemporary art. Different people understand it differently. There’s a lot of artwork out there I myself cannot comprehend. Understanding this kind of art is absolutely subjective.

L.P.: Well, maybe, the main aim of contemporary art is to show different ways of thinking?

L.Q.: Contemporary artists are trying to shock the audience, the shock value being rather controversial actually. I myself do my best not to be controversial. My art is more about us all being together you know.

L.P.: What was your childhood dream?

L.Q.: Good question. Well, when a child, I didn’t know I’d be an artist. When I was 10 years old or so, I wanted to be as well-known, successful, and independent as my father. At this age, you don’t think about starting a family. You think about such superficial aspects as material success and a nice home. I guess that’s what I was dreaming about back then, like any other child. Of course, I’m not talking about starving children, dreaming of beans on the table. When I turned 20, my dream changed — I started dreaming of becoming an independent and successful artist.

L.P.: Once upon a time, all of us were children. Was there a single day, a memorable event, or a lesson in your childhood that you still remember as something valuable for you today?

L.Q.: Yes, there is a story I still remember. One day, our family was on a car journey, returning from a wonderful vacation in the mountains, where we’d stayed at a beautiful luxurious hotel. There were five of us in the car - my father behind the wheel, my mother riding shotgun, my two brothers and me in the back. Father must have been thinking about his past when I started screaming, ‘I’m hungry! I’m hungry! I’m hungry!’ Dad pulled the car over to the highway shoulder and turned round. Looking me in the eye, he said, ‘Son, you’ve never been truly hungry’. He came from a very poor family. And I often think about those words of his. You know it is really important to be able to see all things in perspective.