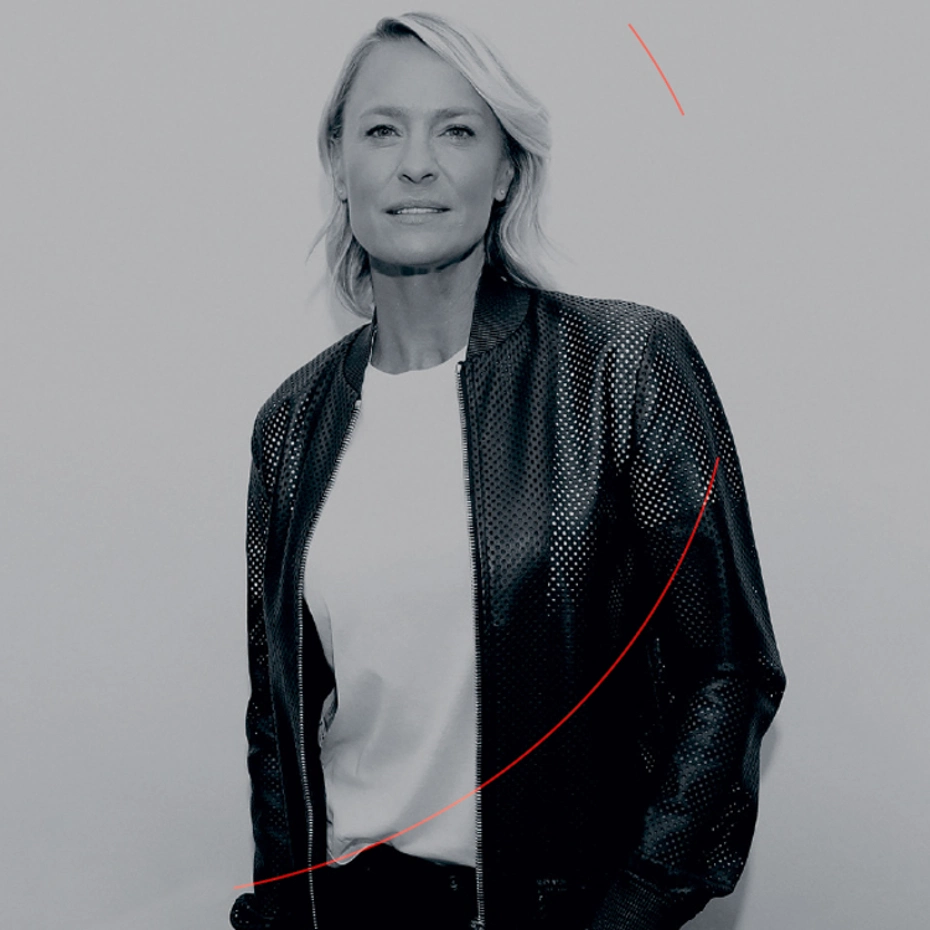

interview — Nelle Holmes

22 January 2021

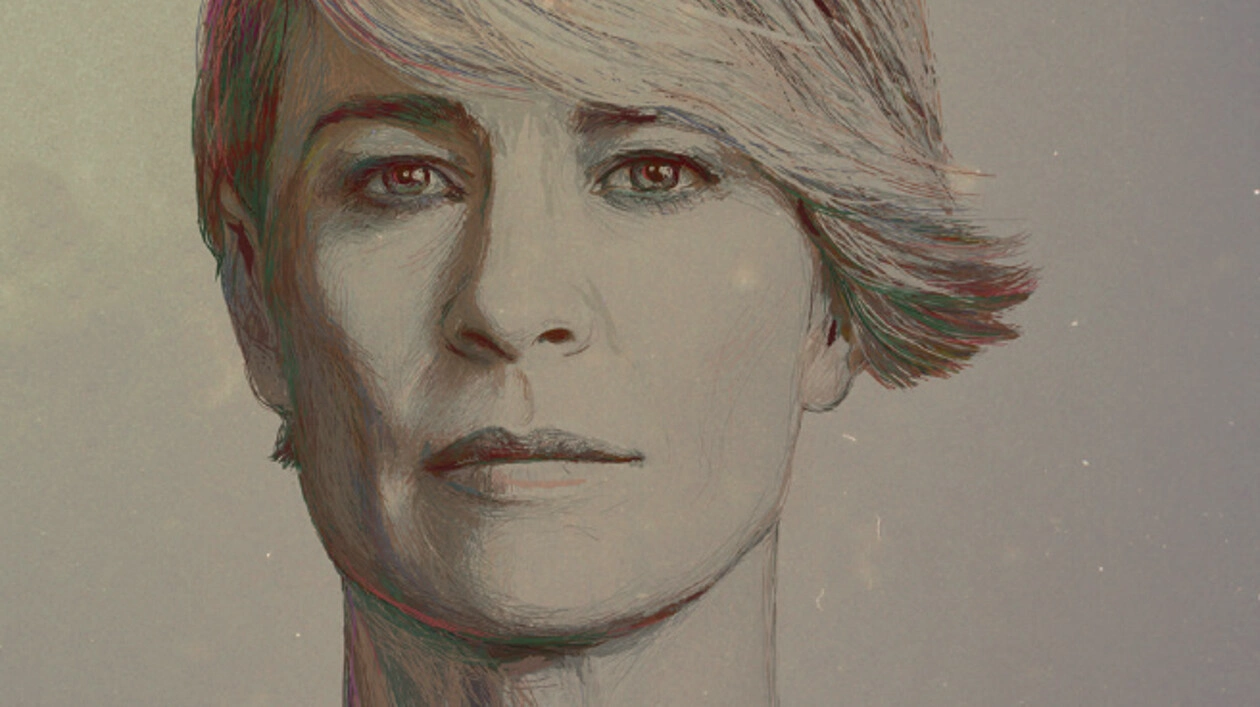

The word ‘actor’ has two meanings, the second having to do with theessence of acting, i.e., playing somebody else and changing the actor’s own personality to convince the audience. What, then, is this personmaking us both laugh and cry? ‘An actor is the facilitator, the vessel the character is fed through’, says Robin Wright to our correspondent Nellee Holmes. This interview leaves a warm fellow feeling for her who takes off all her masks for us.

Nellee Holmes. Life imitating art, when your character – Claire Underwood – became President of the United States, we wondered about the reality of a female US President. So far, we’ve seen none, but Kamala Harris has become the first female vice-president in US history. Having been on such a political show as House of Cards, how significant do you feel it is? Robin Wright. It’s definitely a revolutionary moment that happened yesterday. I feel like we’ve been enduring these four years. I was going to say grinning and bearing it, but we haven’t been grinning. We’ve been bearing it. Finally, it’s time, and the people know it’s even past the time. We do need intelligent, sensible, and compassionate human beings to move in and disarm this political landmine. It has to be done.

N.H. House of Cards is fiction, and its great fun is in exposing political ugliness, manipulation, and corruption. When all that became reality, it was no fun at all. Looking back at that time, what did it mean to you? How scary did it seem to you as an American?

R.W. Scary is the word to be used. It was frightening to see it occurring in the White House a year prior to the actual events. Our writers had already written the script. They had advisors, who had worked in the West Wing for years under the Bush, Clinton, and Obama Administrations, consulting them on a daily basis. The writers would pose questions as they were building the arc of what Claire Underwood was going to do next, and who was going to try and one-up her. That Machiavellian part of the show had to be in every episode: someone trying to get one more rung up the ladder and her knocking them down in a very venial and corrupt way. So, thinking something sounded too ludicrous, our writers would ask the advisors if it was plausible. Most of the time, the latter would say, ‘Ludicrous as it may seem, it’s absolutely capable of happening’. The writers did so time and time again to the point of having to rewrite the text at the last minute, knowing that seven months after the event had taken place, we were going to come out on Netflix. And then, it did happen. It was as if Trump took our great ideas.

N.H. House of Cards was your debut as a director. Why did you take this step?

R.W. I’d wanted to direct films for quite some time but just hadn’t felt ready to jump in the pool, as we say. I wanted my nature to become a little more inquisitive and feel able to be vocal about it. That’s why every day, I sidled up next to the camera operator and the first AC more and more to pick their brains. I asked questions about the lens’s use, the right behaviour in the frame, and such like. As you recall, in House of Cards, we were confined to a very particular style designed by David Fincher. Actually, it was a great beginning as it was learning about cinema and directing in a very structured way. Finally, I just got the bug and felt ready to go. I had such an incredible family of people - the best support system. Everybody wanted me to do my best. They were all gung-ho as if saying, ‘Robin, you should do it as you’ve been wanting to do it. Besides, most of the time, you’ve been basically directing your scenes anyway. So, why don’t you just get behind that camera and try it?’ Of course, I was scared out of my wits, but the team really had my back. They were amazing. That’s how I got the bug. When the show was over, I knew I wanted to direct a feature film. I was very nervous of course. I think that nervousness is going to remain for quite some time. Still, I think it was the jump-start I needed. It was energy, nervousness, and anxiety combined. It was a genuine fear I was not going to get it right. That’s why it was so important to have such an incredible team of producers and creators, architects of the project, around me. It wasn’t just one director but all of them working together. This kind of creative teamwork is all about being able to collaborate, making sure we’re speaking the same language, and having the same vision of the project. There’s nothing greater than that. I had an amazing team of producers on that movie. Every day, those three women were there in that tent watching the playback. I felt they were my right arm. I knew they knew what I wanted to achieve as they wanted to achieve the same thing: the vision, the tone, the theme of the movie, and how we wanted all that to feel. They had been with me all through the pre-production process, talking about it, meeting with the DP, etc. So, we were all on the same page, and I had the utmost trust in their opinions. If I did a take and couldn’t run back to the tent to look at the playback, I would say, ‘Girls, was that good? Thumbs up or down?’ If they said, ‘Thumbs down. You gotta do another take’, I would always trust them. They were never wrong.

N.H. In this industry, it must be really hard to find honest people able to tell you, ‘This one sucks. Better have another go’, right?

R.W. Exactly. It is hard because people probably think, ‘Well, this is not my project. She’s at the helm of the director’s seat’. In essence, they may have felt reticent to tell me the truth, but I demanded it from them. I was like, ‘Guys, I don’t have an ego about this, really and truly. I just want the best moment in every scene to be right’. I really wanted it to be raw, soulful, and about human connection. Thank goodness, I had Demian Bichir! He’s just an incredible soul and an amazing actor. The way he was frugal with his words as Miguel! The way he was quiet, just real Zen! He’d been built to play this part.

N.H. In your previous interviews, you mentioned you wanted Land to bring hope and healing. What was that special connection with the film that made you want to direct it?

R.W. What I connected with most was the words: resilience, hope, and a newfound faith, brought along and given as a gift by a stranger. How beautiful human beings are in this sense! I think we’re all born this way. This script came my way about three years ago, during a time when many countries and ours, too, were experiencing those random shootings, first bi-monthly, then almost bi-weekly. It was becoming the norm. The magnitude of what I felt was like a numbness. We were becoming conditioned to hearing about yet one more case and then about yet another one. I felt the script was really timely. There is so much ugliness, pain, and loss in the world. How do people deal with it? Everybody does it differently. This movie is about a beautiful stranger becoming a friend who just wants to help a woman after her near-death experience in the wilderness. He’s also been through something horrible and life-altering and knows how to guide her through the phases of grief so she could feel comfortable living again.

N.H. The stranger, giving your character kindness and help, was played by Demian Bichir. Was your picking him just a coincidence as it’s a foreigner, an immigrant that helps Edee, even though, yes, he’s a damn good actor, a wonderful person, and a damn handsome man? Or was there a deeper thought to show something we can see in politics?

R.W. Well, it wasn’t just my cultural choice as a director and not because the screenwriter added later on that the man was a Hispanic married to a woman from a local reservation. There’s an interesting fact not many know. An organisation called DigDeep, with many Hispanics on the team, delivers water to those reservations that still have no fresh running water supply. Today, it’s the only WaSH (water, sanitation & hygiene) organisation in the United States. So, our story is based on fact: Hispanics do live in those areas and work for the local people. That’s what the writer, Erin Dignam, knew and educated me about. And I said, ‘That’s perfect. Yes, this man as an immigrant is going to resonate in many ways’.

N.H. The idea of bringing people closer together and making us all feel united rather than separated did resonate with me. I’m sure it resonated with you too.

R.W. I love that you felt that because no one’s actually mentioned, stated, or pointed it out yet. I think it came full circle just like you said. That is the beautiful cohesion of cultures, in which we don’t have to come from the same environment, as all human hearts speak the same language.

N.H. How did your painful life experiences, like the carjacking at gunpoint while you were with your children back in 1997, help you make Edee so real and raw?

R.W. Well, I think an actor is the facilitator, the vessel the character is fed through. So, whether you've literally experienced what your character experiences or not, you have an intellectual understanding of what it means, and what she’s been through. How do you deal with that? What I did resonate with personally was knowing it hurts my best friends to see me in pain. Naturally, it hurts me to see them in pain too. It's the antithesis of selfishness: I cannot stand seeing my friend in pain seeing me in pain. So, I need to depart and try to erase what once was but is no more. The existence Edee once knew is over and gone for good. For her, things will never, ever be the same. Now, it's all about erasing her old self and almost rebirthing, opening to a new kind of faith and a new belief system, and finding love, she thought terminated for ever again with the help of a beautiful human, who comes into her life.

N.H. Have you ever had the feeling of having to learn to live anew?

R.W. Oh, yes, of course, many times. I’ve had to do it coming out of my 20s, 30s, and 40s. It's a natural progression of learning to live in a new prism, having become older and more experienced, and letting go of worrying about small things, etc. We all go through these different chapters of our lives.

N.H. Was there anyone else besides your family and friends to help you?

R.W. I've never had a stranger that became a friend, but strangers did come my way sometimes. I remember meeting a beautiful man on the boat train, going from Bari to Greece back in 1983. I was very young, and he decided to come out and share his life story with me. He felt he had been born this way, but the society was trying to force him to be heterosexual. I remember him opening up my mind to this idea because it had never been discussed publicly. It was not at the forefront of current affairs like it is now. Such was the world. Now, everybody can be free to be who they feel they are. It wasn't that way then. I didn't know that guy. We just rode on the train for two hours, and I never saw him again. But such moments and that kind of education are just unforgettable.

N.H. Were you travelling as a tourist? I think in 1993, you were just starting your acting career, so you were still a model, right?

R.W. It was actually 1983, right after I graduated from high school. I had been cleaning houses to earn money to go to Europe. I wanted to save enough to stay there at least for six to twelve months. That was the beginning of the trip.

N.H. Then you started acting. In The Yellow Rose.

R.W. That's right. I came home from the trip to Europe and got The Yellow Rose. That's right.

N.H. Do you remember the kind of person you were back then compared to what you are like now?

R.W. I was frightfully shy and had an enormous lack of confidence. Still, I knew I wanted to do this as a career. I was drawn to almost the therapy of what acting is about: doing your homework, breaking down and exploring your character, finding the right way to play somebody, sometimes having to learn a new skill. Working on Land, Demian Bichir and I had to learn how to skin a deer and chop wood. We were laughing with glee and saying, ‘Isn't it great what we get to do as actors, what we get to learn, and how expansive that is?’ So, you're always learning about differences in people and different levels of skills in them.

N.H. What shape are your survival skills in now? You live in L.A., which is earthquake country. If another earthquake hits, should I knock on your door for help since you know how to survive?

R.W. No, I wouldn't trust me that much, for the record.

N.H. Hypothetically speaking.

R.W. Hypothetically speaking, if forced to live off the grid, would I manage? After having a mountain man on our movie set teaching us how to do things for real, every day, yes, I would. He actually lives with his wife and children in a cabin without electricity and running water. Such is his choice.

N.H. What would you miss: your smartphone, computer, TV? Could you live without all that?

R.W. I could live without all that. What I would miss is being able to watch films.

N.H. Interesting!

R.W. Yup.

N.H. A little more along these lines, i.e., nature girl vs. city girl. You grew up in the city, so I wonder what nature means to you. Many people have a hard time being alone, surrounded by silence, so to speak, and need some white noise: the radio, TV, or whatever. What about you? Do you feel good all by yourself?

R.W. Well, it's funny because while shooting this movie, Alan Stewart, one of the producers, and I chose to stay in our trailers on base camp. It was literally a stone's throw from the cabin on the mountain. We wanted to live up there and not go back to the city every night. We were really living what we were filming, and it made such an impact. I love being in nature anyway. I've camped out my whole life. My family always went driving across the country and camping in tents. So, living amidst the elements, being around nature and its sounds, per se, wasn't new to me. Alone in my trailer, I sometimes felt a bit scared at night, hearing bears and the sound of the Alberta winds that could get up to 75 miles an hour. With the wind blowing through aspen or pine trees and the sounds of different birds, it was like hearing a new beast every night. So, I started to pick up on the difference in the details, and it was music to my ears. It was not just dead quiet where one would feel desolate. There was a lot of activity going on up there, and I felt I was not alone but had friends and companions around me.

N.H. You definitively possess an incredible physical and emotional grace. How would you rate your physical self on a scale from one to ten?

R.W. That's so difficult because I have to tell you I'm a little bit clumsy.

N.H. Well, that’s why you’re an award-winning actress.

R.W. I mean, it's a different rating if you tell me to put on Louboutins, like I did on House of Cards, every day. That's a little tricky, you know.

N.H. I hope to find you a kindred spirit in terms of emotional grace, kindness, understanding, and forgiveness. How important do you consider all that for yourself?

R.W. I don't know. I think that's who we are. It's our essence as emotional responders to things in life, and I've never been any different. Yes, of course, life experiences have changed me in many ways, altered the belief systems I once had, and psychologically changed my idea of certain things. Still, I think your foundation is always there, and you're always who you are.

N.H. Let’s talk about the current chapter of your life. You are not a rookie as an actress. You’ve been a producer for

quite a while. Now, you are a director too. Your children are already grown-ups and live their own lives, pursuing their own careers. Even though, of course, your motherhood will never end, being a mom is very different now. Are you in Chapter Me, Robin Wright and can explore things you used to put on the back burner when you considered your family first priority, which, I think, has always defined you, and your career second, third, or even fourth one? Is it your me time now?

R.W. Yes, it has been for a while. Like you said, it comes naturally when your kids finally get over the hump of needing you so much. Yes, they will always need me, and I will always be there for them. As to the me period, I think it started around the time of House of Cards and its opportunities. So, I feel very gifted to be able to explore more projects and become more creative in adapting book to screenplay, etc.

N.H. Did you feel scared when Dylan and Hopper opted for modeling and acting, basically following you in your footsteps?

R.W. No. They grew up on sets ever since the time they were newborns. Both their parents have been in the industry since we were teenagers. So, it’s only natural both of them should be really good actors. They’ve watched a good many great movies and experienced all kinds of cinema to break up the effect of such silly shows with no substance as Harold and Maude.

N.H. What’s your children’s favourie film or show featuring Robin Wright?

R.W. Frankly, I have no idea. Truthfully, I don't even know if even one of them has seen Forrest Gump or The Princess Bride. Oh, yeah, again, this is mom’s feelings: they're always very supportive and want to see what I did, but it's not the first thing on their agendas. You know what I mean – for them it’s: ‘Been there, done that. We know this is what they do for a living. They’ve been doing it since we were born’.

N.H. Well, The Library of Congress considers The Princess Bride and Forrest Gump culturally, historically, and esthetically significant, so they are to be added to the National Film Registry. Your children should see them for sure.

R.W. Both of them are being submitted for that?

N.H. Yes. They are both culturally important. Were you aware of it?

R.W. I knew they definitely had the essence. The Princess Bride, with the greatest William Goldman’s humour, is a depiction of true love. You can’t go wrong with that. Forrest Gump could have been a really sentimental film. The originality of this movie is all about human kindness. Winston Groom wrote the story, while Bob Zemeckis and Tom Hanks translated it seamlessly on the screen. Nobody but Tom could have played that part.

N.H. You’ve played wonderful and strong women who have something significant to say and do lately. To me, it speaks volumes. These roles are very different from those romantic characters you used to play when you were younger. Do you still have fond memories of those times? Do you ever miss that nice romanticism?

R.W. Yeah, but now, my desire is to dabble in comedy, not only as an actor but definitely as a director. That’s what I’m going to pursue. I’m ready to laugh.

N.H. House of Cards was a Netflix series, but back then, nobody knew the words ‘streaming’ and ‘streamer’. Saying yes to the project, did you know that you were stepping into something that would open up a whole new universe and become the future of entertainment?

R.W. With the streaming? I did because that’s how David Fincher, who’s so smart and such a brilliant director, proposed it to me. He said, ‘We are going to be a part of something revolutionary. It’s called streaming, and it’s going to be a way to the future of how to view content’. I trusted him completely and jumped on board. And he was right.

N.H. Wow! Back then, in 2016, you were one of the first actresses to demand pay equal to that of your male co-star. It was something we all wished, but very few had the courage to speak about it openly. You had and did. How significant was it for you? Are you aware of the fact that your action made you a role model?

R.W. It’s pretty straightforward. I’ve always believed that women and men should have equal pay for doing the same job. I’m sure everyone agrees with that.

N.H. I’m not sure if you’re still involved with Pour Les Femmes, The SunnyLion, and Raise Hope for Congo. How important is it for you to somehow take part in protecting human rights and making the world a better place?

R.W. It’s always been important. I think it was, sort of, embedded in me at a very young age. I was only five years old when someone asked me what I wanted to do for a living. I said I wanted to be a frontline worker, to work in a refugee camp as a doctor or a nurse, and help people in need. We instilled that in our children, so they’re great civic servants as well. I hope that answers your question.

N.H. How did you get involved in helping Congo?

R.W. I was informed about the crisis in eastern Congo in 2011. I learnt that leading electronics companies purchased minerals mined in this country and used them to produce cellphones, computers, toasters, microwaves, and everything else for everyday life. In the meantime, all kinds of armed groups had been devastating the mining areas to take control and generate revenues to further fuel the conflict, on top of everything, using sexual violence against Congolese women and girls as a weapon of war. So, I thought it was our duty and responsibility as consumers of all these products to raise public awareness of the conflict. At the time, every 48 minutes, another Congolese woman was being raped, her husband recruited by an armed group, leaving her, basically, incapacitated to take care of her children by herself. I was on House of Cards at the time but still did what I could. I went to Washington, D.C. and got in touch with some senators to educate them about the situation. All of them were moved and shocked. Many didn’t know the details and everybody’s connection with the Congolese crisis. This way, I helped John Pendergrass, an old friend of mine and a co-founder of The Enough Project running the Raise Hope for Congo campaign, to move some major mountains, so to speak. Still, my going to D.C. did not produce enough volume. So, one of my oldest and dearest friends, a clothing designer, suggested we should do something we’d always wanted to. She said, ‘We love pajamas and the symbolism of getting in bed, feeling secure and safe. It’s our God-given right while the women of Congo are deprived of it’. We used the idea as our ethos, and it helped to raise more public awareness of the problem. We found consumers who liked our product and felt great about helping Congolese women in need bringing life and hope back to them by purchasing a pair of pajamas, as part of the proceeds was going to help those women to have sustainable lives again. So, it was a twofer.

N.H. I suppose, the pandemic may have become a threefer for you. Have the sales of your pajamas gone up?

R.W. Yes, everyone has been living in pajamas for the last 11 months so that’s been a real coup for us.

N.H. Speaking about role models, I just cannot let you go without talking about Wonder Woman. Your role in that film was minor. Still, it must have been a mind-blowing message for ‘the little ones’ of all ages. What is your role in Wonder Woman to you?

R.W. The message of this movie is very important. The new generation is growing up with social media awareness, knowing how to play in them. That exposure is very daunting. With their faces stuck in the screens all day long, young people lose a lot of their childhood. We never had that stuff, learning about morals and ethics from our parents and mentors. So, we wanted to bring youngsters back to the roots and allow them to know about truth, honesty, and love as the only right way of life. That’s what the message of Wonder Woman is all about: there must be no lying to our little ones, no pulling wool over their eyes, and no scheming of any kind, but love and justice. And I had so much fun playing my role in partnership with that darling little girl. She was just incredible.