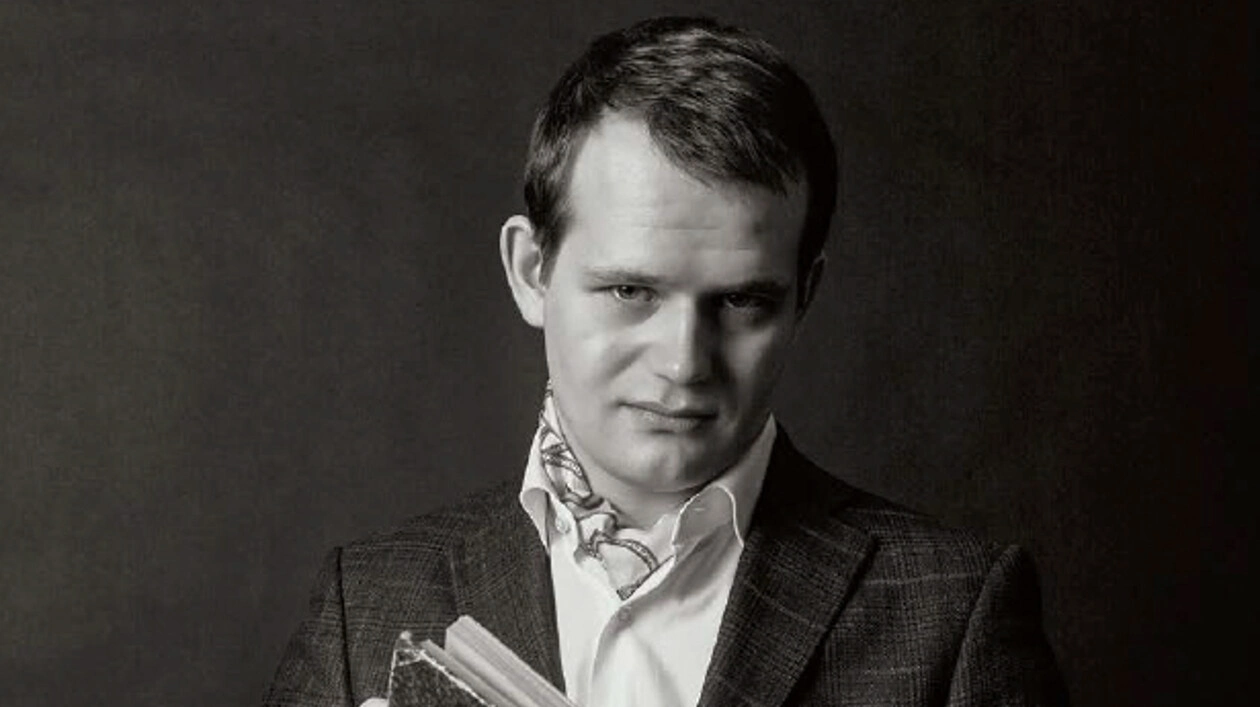

U-t-o-p-i-a … Six letters in all, for this thing that is not. And how many modifications and mystifications have there been? Why? Perhaps, because everyone who carries "the home of all paint pots" in their history has taken a bite and spit it out as useless illusions? Or perhaps humanity finds it dreary not to dream of perfection, of something non-existent, but so greatly desired. Residing in a single person, we call it a dream; having infected many, it's a revolution. And then, utopias are replaced by anti-utopias, as the next image of "paint pots". On humanity's "golden books," and on the consequences of expecting some bright future to deliver rivers of milk and wine, we present our returning columnist, Vadim Veterkov, whose exquisite style and depth of thought give us, again and again, to peering into and pondering his words.

The Golden Book (thus begins a title, which in its English translation, consists of no fewer than 21 words, the last of which is Utopia) of Thom-as More set the bar high for its genre, but the sixteenth century was fertile ground for new political ideas, rival-ing even Plato's Greece, the origin of all utopias. By that time, intellectuals in Europe already outnumbered the non-intellectuals in power, and to the great displeasure of the latter, thelit-erary and political machine was hard at work, trying to change society.

Of course, texts similar to Utopia had been written prior to Thomas More. Some, like Plato's Republic, were even political. But they were, most often, rather innocuous, in the sense that while they may have been written for political purposes, the most likely beneficiary would have been the existent order. The preaching of salvation, at its outset, raised certain questions, which inquisitors primarily would pose to subjects bound to red-hot grates. "Quae sunt Caesaris Caesari et quae sunt Dei Deo", and this "eternal kingdom": is this to mean that Caesar himself is divine?" But then, later, it became the basis for the new medieval world order. Or you had hungry medieval peasants in the 13th century who had only the foggiest idea regarding the existence of philosophers or intellectuals, but for whom the countries of Cockaigne or Schlaraffenland cut a very clear picture indeed. The entirety of the tale describing the economic and political structure of the region has failed to reach us, though it is known that in the land of Cockaigne, alongside the roads there were tables arranged, draped with white tablecloths, bursting with free food. There were rivers of wine, and everywhere, beautiful women who willingly consented to all comers, while sacrificing no respect in so doing. There, sleep was rewarded with pay, while work was met with ridicule, even beatings. How a medieval resident from eight centuries ago would have been able to predict the appearance of the Tarentaise Valley resorts is a great historical mystery, much like the Antikythera mechanism, all extant versions of texts on Cockaigne, the end is more or less the same: "…If things are well for you in your place, abandon them not, for you will only come to loss in seeking out change". That's quite the placation. After having reached the lord's castle, pitchforks in hand, opting instead not to demand change and sausages. When it comes to Cockaigne the country, it is Peter Breughel who bore the responsibility of offering European culture's answer in visualised form. The Peasant that he was, with the painting of the same name, his is a rather exhaustive illustration of the project's political connotations.

All, or almost all, of the classic utopian works of antiquity, the Middle Ages, and the early Renaissance, are more about where than who. And they're more about what was necessary than about how that could be done. This made the utopias of earlier times popular but politically feeble texts. When later, in The Prince, Niccolo Machievelli dealt with, snidely, the projects of these non-existent states, it was precisely these features that he would ridicule. Utopia is always somewhere we are not, somewhere we will never be.

The culture of modernism did away with this melancholy thesis. "-Isms," which arrived in the 19th century, and by the 20th had worked themselves into politics and literature, did not leave room for wishes and dreams, and concentrated instead on what was necessary. The time for long-winded, non-binding discourse had passed, and would not return the new utopians would demand action. Modernist ideologies (whether artistic or soci-etal didn't matter) had arrived at a sufficiently clear idea of how everything should be arranged so that all would be well. With schedules and job descriptions. Those who believed they wouldn't be so well off could be sent to camps, or quarantined in prisons, as extremists unwilling to accept the conditions of a free society. When they had disappeared, one way or another, all would be better off. People would build their utopia themselves. Under the wise leadership of other, specially qualified, people, of course. At this point, Utopia becomes a fiction, and one, like everything associated with modernism, of science. The place no longer plays a role; what's most important is a person. Stories about a better society will gain strength and, in doing so, will become a threat. Including to those who should be serving.

For example, the science fiction of the countries of the socialist bloc, which were intent on building perhaps the most ambitious "-ism" in history: communism, a powerful cultural phenomenon. The novels of Bulychev, Efremov, and, most importantly, the Strugatsky brothers, are likely no less influential than the classic Russian literary can-on, and, proportionally, are no less important in this area of the world than the works of Saymak, Heinlein or Le Guin are in the West. In the case of the Strugatskys, their influence on society has been particularly great.

Those familiar with their oeuvre will know their utopia's name: Noon. In the 22nd century, humanity, having built communism, and being fantastically de-veloped technologically, has commenced building com-munism on the new worlds that have been discovered. For this purpose, there's been established something between a state and public service the Institution of Progressors, people whose work it is to advance progress on backward worlds. Earth being, of course, the model. From time to time, a progressor on this or that world is found out, and the aboriginal who has done so is faced with a choice: either to assist the Earthling progressor, or to stand in his way. For a good guy, of course, there is no other option but to take the side of Earth, and begin building the bright future. What does this look like? The aborigine is shown: teleportation, material abundance, medicine that borders on magic. From time to time, the newly enchanted aborigine perishes for the sake of a good cause and the building of a new world.

An excellent point of view, when you imagine yourself as the progressor. Fairly common in the Soviet Union of the 50's and 60's. But when society changes, and its stated goals begin to differ from what people experi-ence all around… Utopia, despite being built entirely on fantasies, does not forgive lies. In the late 80's, romantic reformers, tired of hypocrisy and stagnation, began to look for new, positive images. And they would be found in the works of those who'd created the Soviet utopia. They would actually find progressors to whom they no longer related. Remaining in the best, literary sense, "good guys", they would discover that the utopia planned on paper was very different from what was going on in practice. The consequences, not even social or economic, but psychological, as we know, would be extremely sad. A society disillusioned with the building of one utopia has an extremely small likelihood of getting to work on the next. Of course, the most frenzied of utopians will not be hindered, and will still attempt construction on something, however diminished in scale. Even a civil, courteous remembrance of the past will not slow them down. Though the feeling won't be the same.

The influence of utopias has begun to wane. The contemporary architecture of Las Vegas does not teach life; the bright new world of the digital economy has heavily coloured the work of writers ranging from Lois Lowry to Orwell, whose prophesies, subject to endless digital iterations, have been rendered unrecognisable; somewhere far off, missiles and bombs force ever deeper into a wasteland those who wished to build, unhindered by the opinions of others, the kingdom of God on earth.

There isn't a moral to be extracted about the fate of utopias. But there is advice to be had: treat gently those who wish to bring about utopias in practice. But to those who conjecture about utopias but aren't hurrying to build a better world, give encouragement. In any case, it's just a river of wine.